TABLE OF CONTENTS

Modern research indicates that Giuseppe Morello and Ignazio Lupo may have led separate crime families.1 The “Morello Gang” referenced on this page is a combination of those two groups.

Giuseppe Morello was born at Corleone, Sicily, in May 1867. His entry into the local Mafia was likely facilitated by his stepfather Bernardo Terranova and uncle Giuseppe Battaglia, members of the Corleone borgata (a term meaning borough or village, within the Mafia it defines a clan or crime family).2

At the age of twenty-five, Morello left Sicily for America. His departure occurred around the time he was accused of killing a witness to a murder in Corleone.3 He arrived in New York in 1892, followed a year later by his family which included his half-brothers Nicola, Vincenzo and Ciro Terranova. After spending a year in New York, the family moved to Louisiana and then to Texas, before finally returning to New York around 1897.4

Morello first attracted the attention of the Secret Service in March 1899, after a letter he’d sent to a Boston counterfeiting gang was intercepted.5 He was suspected of distributing poor quality counterfeit notes and was arrested the following year on East 108th Street. Papers found in his possession connected him to Calogero Gulotta, whose son Gaspare was later involved the New Orleans Mafia. Morello was discharged after no direct connection could be made between him and the sale of counterfeit notes.6

In November 1900, Morello leased a saloon and basement at 445 Thirteenth Street,7 but gave up the business after just seven months. He later started a restaurant in the rear of the saloon at 8 Prince Street,8 a known hangout for counterfeiters and under regular surveillance of the Secret Service.

Morello led the Corleonesi crime family in New York, which later divided into what are known today as the Genovese and Lucchese Families.9 His power was first indicated in July 1902, when he was reported to have “approved” the murder of Brooklyn Mafioso Giuseppe Catania. Catania liked to drink and “talked too much when drunk.” His mutilated corpse was eventually discovered dumped in Brooklyn in a similar fashion to the Barrel Murder.10

Born at Palermo in March 1877, Ignazio Lupo worked for his father in the grocery business. In 1898, while managing one of his father’s stores, he killed a local businessman during a disagreement. He fled to New York, where he began working with relatives in the wholesale grocery business.11

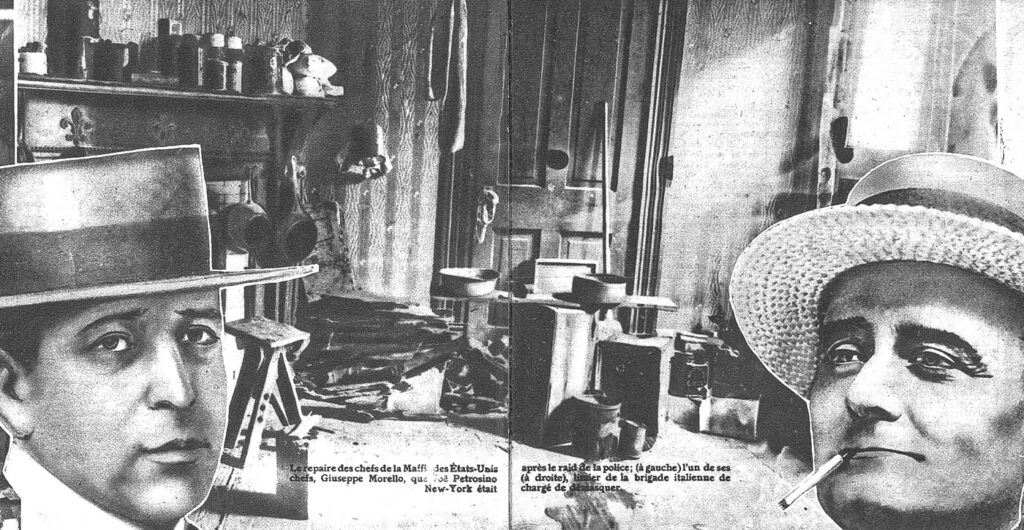

Lupo became a brother-in-law to Giuseppe Morello when he married Salvatrice Terranova in late 1903.12 The press often referred to him as Morello’s lieutenant, but modern researchers argue that the two men actually led separate crime families, Morello heading the Corleonesi-based group and Lupo leading a Palermitani family. The police described Lupo as “the treasurer of the Mafia Society of the United States, or at least to that section of it to which Italians in the country who come from Palermo belong.”13 His organization was later headed by such names as Carlo Gambino and John Gotti.14

Lupo was described as a delinquente raffinato (refined delinquent). A well-dressed, soft spoken, urbane and affable businessman, he wore rings on both hands and was found to carry a “big blue barreled revolver of the latest type of one of the best manufactures.”15 His store at 210–214 Mott Street, was described in The New York Times as ‘‘easily the most pretentious mercantile establishment in that section of the city, with a stock of goods over which the neighborhood marveled … Lupo’s horses and delivery wagons were the best that had ever been used in the neighborhood.” The turnover was estimated between $500,000 and $600,000 a year.16

William Flynn, chief of the Secret Service, explained that Lupo forced local businesses into trading with his wholesale stores under the threat of their own businesses being bombed. Flynn also believed that Lupo was using olive oil cans to import counterfeit notes from Sicily, but after impounding his shipments found no evidence to support the theory.17

In November 1908, Lupo left New York owing up to $100,000 to his creditors. As many as seventeen other Italian grocers also disappeared, with combined liabilities estimated at $500,000. The stores had been emptied of their stock, which was later tracked to warehouses across the city, with some goods having been shipped to Italy.18

The entire conspiracy was claimed to be the idea of Attorney Philip Saitta, who had represented the Lupo-Morello combine during the Barrel Murder trial and had previously represented New York fruit importers in front of Congress. The assistant district attorney stated, “The Police Department of this city, as well as many well-informed businessmen, believe that [Saitta] has been the mastermind and legal adviser to the Mafia, and has been in close association as adviser and friend of some of the most dangerous and notorious criminals for years.”19

Lupo returned to New York in late 1909 to face his creditors. Before any charges were bought, he was arrested with Giuseppe Morello in connection with a large counterfeiting scheme.

The Morello Gang’s early focus was on counterfeiting US currency. A dangerous occupation that would result in them becoming the focus of the New York Secret Service branch with agents specially trained to detect bogus bills and covertly track street pushers.

After traveling from New Orleans to New York, Sicilian Calogero Maggiore was arrested in June 1900, along with Giuseppe Morello, for distributing counterfeit five-dollar notes from an East 106th Street headquarters. Correspondence found on Morello connected him to New Orleans and other US cities, but he was eventually discharged due to lack of evidence.20

In 1902, Joe Petrosino, of the NYPD, received an anonymous letter about a counterfeit coin plant in New Jersey. The investigation led to the arrest of Vito Cascioferro, “probably the most powerful Sicilian cosca (clan) leader of the age.”21

Petrosino’s tip-off led to the capture of a gang thought to be responsible for 75 percent of counterfeit coins in the region. The arrests included Vito Cascioferro; Stella Frauto, an experienced female counterfeiter; Andrea Romano, the owner of the Prince Street saloon; and Salvatore Clemente, who became an invaluable informant to the Secret Service through the next thirty years.22

Cascioferro managed to escape conviction after some witnesses failed to identify him and others failed to appear at all.23 The following year, he was tracked around the city by Secret Service agents. They observed his meetings with many Italian counterfeiters, primarily Giuseppe Morello and members of his gang. In March 1903, he was seen trying to arrange passage back to Sicily before he disappeared from the city.24

The alliances that the gang formed in these counterfeiting schemes show a mixed bunch. The 1900 arrests list a mixture of Italians and Irish criminals, and the gang in 1902 had been led by a woman. Working with already established gangs in New York was a necessity likely born from the technical and network requirements of the counterfeiting business.

In April 1903, the discovery of a body stuffed into a barrel led to the capture of Morello and Lupo. The gang’s counterfeiting efforts ceased and did not start up again until 1908 when they began a scheme printing hundreds of thousands of fake dollars. A scheme that would send the pair to Atlanta Penitentiary.

Giuseppe Morello started a real estate company in 1902, ‘The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi’, the company was involved in the construction and selling of properties in New York. The names listed on the incorporation as directors were Antonio Milone — a man who would later be involved with their counterfeiting schemes; Marco Macaluso, father of 1960s Lucchese Family “consigliere” (advisor) Mariano Macaluso; and Frank Badalato, who would later own the hay and grain store located next to infamous East 108th Street property known as the “Murder Stables”.25

Primarily a banking and real estate company, it traded New York real estate and constructed its own tenements in the Bronx. Shares in the company were sold to southern Italians with the expectation of dividends, but the company ran into serious financial problems around the time of the 1907 Bankers’ Panic. Anxious investors threatened to kill Morello while contractors and lenders started legal action against the business. Morello and Lupo started a counterfeiting plant in Highland to help pay off the debt. The plan would eventually land them both in prison.26

At around the same time as the The Morello Gang’s construction troubles, Lupo began a huge fraud scheme using his wholesale network. He built an impressive chain of wholesale grocery stores during his time in New York. William Flynn, chief of the Secret Service in 1914, described how Lupo used his network of businesses:27

The small Italian grocers of the district were forced to buy their supplies from this store. If they did not their establishments were in danger of being wrecked by bombs or burned. Even worse, their children might be kidnapped or themselves slain. By intimidating the local grocers into trading at their wholesale store, Lupo and Morello accomplished a double purpose. They swelled their so-called legitimate profits and were able to get rid of some of the counterfeit money.

It was often reported in sensational articles that Morello was the “Head of the Black Hand.” While he was found with letters connecting him to extortion of wealthy Italians, no arrests were made as a result28, but there are some connections that can be made.

Antonio Comito, a witness who testified against Morello and Lupo, recalled a story told to him by Nick Sylvester. Although Sylvester was a low-ranking member of the gang, he had blackmailed a man on Mott Street using threatening letters. This, he told, was done along with Giuseppe Morello’s half-brother and son.29

He was a fool and told the police. We did not know that though and when he failed for a third time to give up the money we went there late one night and threw a big bomb through the window of his store … We were arrested but it had been dark and we had arranged things so carefully, even having the letters written by others and never having him see or know us, that there being no eye witnesses a good lawyer who helps us much in New York got us free.

In 1906, John Bozzuffi, a successful New York banker who had acted as a public notary for Morello, was facing demands for $20,000 for the return of his son. The boy managed to escape and identified his captor as Ignazio Lupo. Lupo was taken into custody but soon released due to a lack of evidence. An unrelated investigation into a Mafia killing in Partinico, Sicily, led to the discovery of a “direct connection of the Sicilian Mafia with the Black Hand of New York.” Papers found in the home of Nunzio Minore linked him directly to the Bozzuffi kidnaping, the US Black Hand and the Sicilian Mafia. 30

In 1909, when Morello was arrested in connection with counterfeiting, a series of Black Hand letters were found at his home.

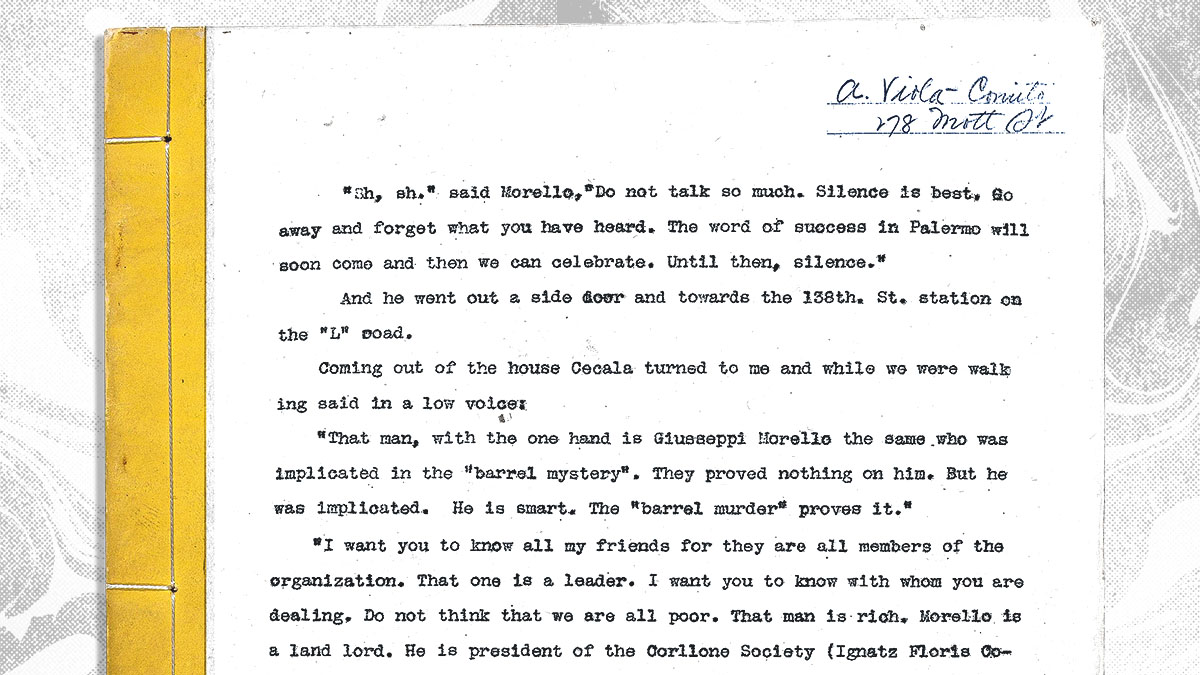

Antonio Comito, who appeared as a witness in 1910, spoke about Morello’s leadership:31

The leader — a one armed man named Morello … One alone never carried out the orders of the ‘superiors’. To do so took to great an amount of courage. Such work was always done by three or four, directed by a ‘corporal’, who was put in charge of the ‘work’ at hand by the head — called the ‘President’. He, from a distance directed the execution of the four members’ work. Always from a distance so that should their work be discovered by the police it would be easy for him to make an immediate report. The ‘head’ would inform all the other members and they would hold counsel and deliberate what to do. Under false names members of the organisation have even appeared as witnesses for the prosecution only to go upon the stand, refute all their previous statements and deny their ability to attach the defendant in any way with the case in hand.

Comito also recalled a conversation between himself and Antonio Cecala from the gang:32

I want you to know all my friends my friends for they are all members of the organisation. That one [Morello] is the leader. I want to know with whom you are dealing. He is president of the Corleone Society [Ignatz Florio Co-Operative] and has in his power, four buildings, amounting in value to over one hundred thousand dollars.

Morello knows how much money he has given to detectives, when and where it was given and the names of those who have taken it. He has always gotten out of everything in which he was implicated … When the order is given to arrest Morello, policemen whom he had fed always will warn him and he will hide.

There are twenty of us who have organised this affair. Others higher up in famous places know of it. They will receive their share. Should anything slip and we get into trouble there will be thousands of dollars for lawyers and we will be freed … We are big, bigger than you know. You will know perhaps, later on, about the many branches of our society, and how it is possible for us to do things in one part of the country or world and have the other half of the affair carried out so far away that no suspicion can possibly come to us. After you have obeyed and seen some inkling of our power, you will be glad to become one of us.

As well as enjoying the protection of corrupt NYPD officers, the gang is supposed to have held some political influence. In 1903, after the collapse of the ‘Barrel Trial’ against the gang, Secret Service records noted a conversation between Pietro Inzerillo and one of their undercover agents. During the conversation Inzerillo claimed that his release from the trial was due to the actions of Congressman Timothy Sullivan.33

In June 1912, whilst Morello and Lupo were trying to secure their release from prison, William Flynn of the Secret Service was interviewed about the gang’s political power:34

Mr. Flynn was asked if the band had any political influence. His answer was: ‘The strongest I know of. It is almost Impossible to combat it. It comes from both political parties.’ He then was questioned as to whether this influence would be strong enough to swing a Congressional Investigation of the Secret Service in the hope of crippling it. ‘It is possible,’ said Mr. Flynn.

Speaking about the gang, Flynn was also quoted in 1912:35

These bands are protected by money and by political influence. I do not blame either political party exclusively. Both protect these bands for one reason or another. Of course, besides being able to collect thousands of dollars from Italians and Sicilians, they are able to sway hundreds of votes by terrorising citizens. The police are to a certain extent powerless because of the powerful backing these men get from politicians.

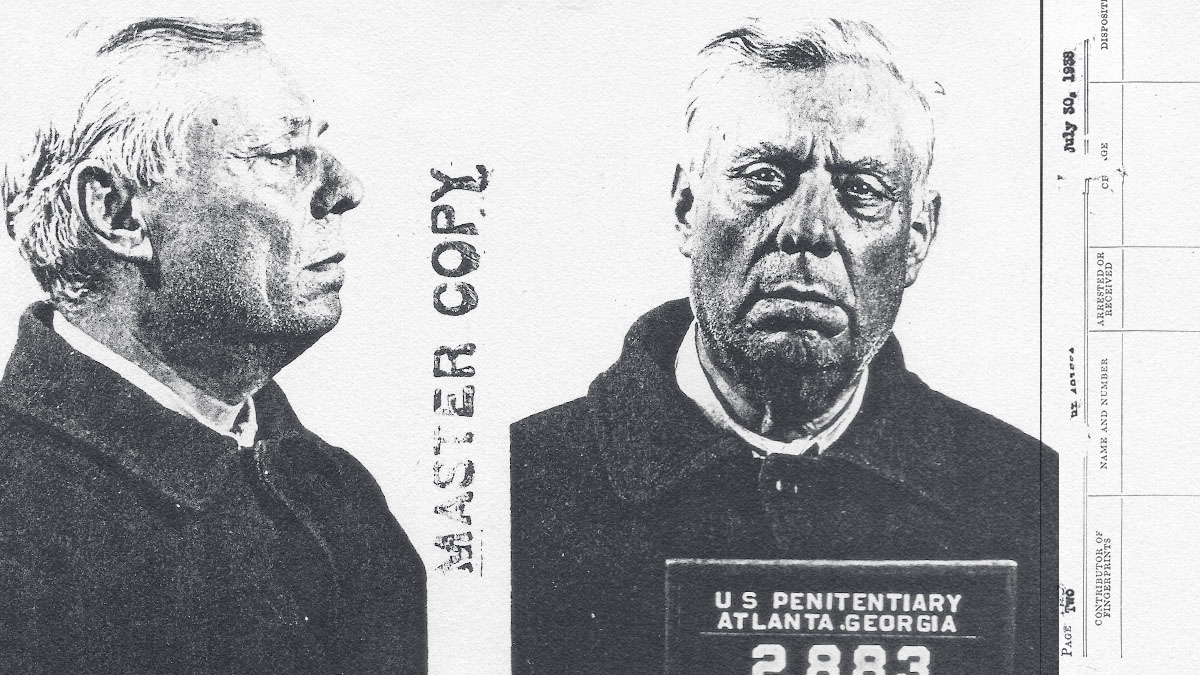

Lupo and Morello were released from Atlanta Penitentiary in 1920. Morello had lost close family to the gang feuds during his incarceration, including his half-brother Nicola and his son Calogero. Upon his release, he quickly eliminated Salvatore Loiacano, who had risen to lead the Morello Crime Family. Morello had disapproved of his handling of the clan, possibly due to Loiacono’s subordination to boss of bosses Toto D’Aquila. The killing sparked the beginning of a bitter three-year feud among the D’Aquila, Morello and Schiro Families.36

Lupo, Morello and other allies made a short trip to Palermo in late 1921.37 The reason for their voyage was later described in a confidential Secret Service report:38

When Lupo and Morello were convicted fifteen or sixteen years ago on our counterfeiting case, new leaders arose. Since that time they have grown very strong and very popular. Upon the release of Lupo and Morello they tried to come back into power, but the new organization here in America would not permit this. Consequently, Lupo and Morello and a few of their old ‘standbys’ went to Sicily, taking it up there with the main headquarters endeavouring to be put back in power. They also refused … since that time Morello has moved to the West Side and both he and Lupo are living behind bars and shutters. Their assassination is expected momentarily.

Further detail was given in the memoirs of Mafioso Nicola Gentile. He explained that Lupo, Morello and ten others had been condemned to death by boss of bosses Salvatore D’Aquila at a meeting of the US Mafia’s General Assembly. “It was a question of power. D’Aquila was a very authoritative figure and that meant that those who didn’t support him were condemned to death.”39

Giuseppe Morello kept a low profile after his release from Atlanta Penitentiary. This was mostly due to the feud with D’Aquila. A consequence of Morello’s caution was a separation between his activities and the Secret Service’s network of spies. Although he was reported to be still active in counterfeiting40 the Secret Service did not connect him directly to any of their investigations. The warring families made temporary peace in August 1923 after a large conference at Highland, New York. It was agreed that Lupo would be brought back into the Fratellanza – but Morello was still to be excluded.41

Conflict between the Mafia Families flared-up again in 1928. Fifty-year-old Mafia leader D’Aquila was killed during a family visit to a doctor’s office in Manhattan. The assassination was ordered by Giuseppe Masseria, who replaced D’Aquila as the new boss of bosses, with Giuseppe Morello as his second in command. Masseria’s reign was brief. Both he and Morello were killed in the “Castellammarese War,” a violent struggle for control of the Mafia which began just two years later.42 Morello was killed in August 1930 in Harlem at East 116th Street, bringing the career of the first boss of the US Mafia to an end.43

Lupo, who had relocated back to Brooklyn in 1927, drifted back into his old habit of extorting store owners. Following Frankie Yale’s death, he acquired control of the Brooklyn bakery racket and was also suspected running policy games in the area. He was arrested at his son’s bakery and returned to Atlanta Penitentiary in 1936 as a parole violator. He was to serve the remaining twenty years on his 1910 counterfeiting sentence.44 Lupo died in 1947 three weeks after his early release from Atlanta. He was later made the subject of the first episode of “Treasury Men in Action,” a popular 1950s television series based on the US Treasury Department.45 Ciro Terranova, the last remaining brother of the Morello family, remained a figure in organized crime until he passed away in 1938.46

The Secret Service’s penetrating investigations into Lupo and Morello, and the exposure the press gave to their violent exploits, provide a detailed thread through New York’s early Mafia history. The Secret Service’s recruitment of informers had ultimately led to the pair’s downfall. Their imprisonment and loss of power in 1910 had been due to a case built around the testimony of Antonio Comito. Although Comito was an outsider to the group, a lack of organizational security had put him in direct contact with the US Mafia’s leadership.47

- Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. [↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van‘t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 42-43

Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 52[↩] - General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. Numerical Files, 1906 – 1910. M862 Roll 845. Giuseppe Morello criminal record.

Flynn, W. J. (1919) The Barrel Mystery. New York: The James A. McCann Company. 243-261[↩] - U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Guiseppe Calicchio et al, Transcript of Record. Ciro Terranova testimony[↩]

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter referred to as NARA), RG 87, Daily Reports of Agents, (hereafter referred to as DRA). William P. Hazen. Vol. 5 (Mar 18, 1899) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William P. Hazen. Vol. 9 (Jun 9, 12, 18, 28 1900)

Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 58[↩] - Real estate record and builders’ guide (1900) Vol.66. New York: F. W. Dodge Corp. 589[↩]

- Guiseppe Calicchio et al, Transcript of Record. Ciro Terranova testimony[↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 90[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn (Jan 4, 1903)

The Evening World (Jul 24, 1902) 1[↩] - U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Giuseppe Calicchio et al. 450, 462[↩]

- Manhattan marriage certificate 251 (1903) [↩]

- The Baltimore Sun (Apr 17, 1903) 8[↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van‘t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 7[↩]

- Flynn, W. J. (1919). The Barrel Mystery. New York: The James A. McCann Company. 28

Frank Marshall White (1913). A Famous Tragedy of the Black Hand. Pearson’s Magazine. Vol. 30.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Jan 12, 1904) 20[↩] - New York Times (Nov 13, 1909)

New York Times (Dec 5, 1908)

The United States of America vs. Giuseppe Calicchio et al. [↩] - The Washington Post (May 3, 1914) 8

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 8 (Feb 14, 16, 1903) [↩] - Black, Jon (2014). The Grocery Conspiracy. https://www.gangrule.com/articles/the-grocery-conspiracy [↩]

- Brooklyn Citizen (Jul 19, 1903)

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Apr 13, 1914)

New York Tribune (Apr 14, 1914)

The Lloyd Sealy Library of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Trial Transcripts of the County of New York. Court of General Sessions 1883–1927. #1857 Philip S. Saitta (1914-3-20)

Black, Jon (2014). The Grocery Conspiracy[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William P. Hazen. Vol. 9 (Jun 9, 12, 18, 28 1900) [↩]

- Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 40[↩]

- The Scranton Republican (Nov 28, 1902). 2

Buffalo Courier (Dec 7, 1902) 2

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn & New York Volumes (1902~1930)

Warner, Santino, Van‘t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 5[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 6 (May 29, Jun 4, 1902) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 6 (Mar 23, 1903) [↩]

- The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi. Certificate of Incorporation. 1902

Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 46[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 28 (Nov 22, 1909)

Flynn. The Barrel Mystery. 30, 184

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn (Feb 10, 1913) Statement of Salvatore Cina

Central Union Gas Co. vs Browning (1911)

John A. Philbrick vs “Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi”, et al. (1908) [↩] - Black, Jon (2014) The Grocery Conspiracy. https://www.gangrule.com/events/the-grocery-conspiracy[↩]

- El Paso Times (Apr 18, 1903) [↩]

- Confession of Antonio Comito. Lawrence Richey Papers. Black Hand Confessions, 1910. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library.[↩]

- New York Times (Mar 7, 8, 1906)

Certificate of Incorporation of the Ignatz Florio Co-operative Association Among Corleonesi. 1902

The Washington Post (Mar 16, 1906) 1

The Sun (Mar 9, 16, 1906)

St Louis Post Dispatch (Mar 31, 1907) 2

Chicago Tribune (Apr 1, 1907) 5

Bisbee Daily Review (Apr 21, 1907) 11[↩] - Confession of Antonio Comito[↩]

- Confession of Antonio Comito[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. Flynn. Vol.9 (Apr 26, 1903) [↩]

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Jun 3, 1912) [↩]

- New York Herald. Jun 30, 1912.[↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van‘t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 63-64

“My ten biggest man hunts. William Flynn” Albuquerque Journal (Mar 13, 1922) [↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol. 76 (Dec 2, 1921) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol. 80 (Oct 5, 1922) [↩]

- Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 155

Warner, Santino, Van‘t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 64, 68[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol. 83 (Mar 20, 1923) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol. 85 (Aug 28, 30, 1923) & (Sep 21, 25, 1923) [↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van‘t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 88-89

Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 157, 181, 185

Bonanno, Joseph, and Sergio Lalli. A Man of Honour: the Autobiography of a Godfather. Deutsch, 1983. 100 (morello 2nd in command) [↩] - New York Times (Aug 16, 1930) & (Apr 16, 1931) 1[↩]

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 204, 230/40/1/3 box 956 (Ignazio Lupo).

Brooklyn Times Union Thu Jul 16 1936. 2[↩] - Treasury Men in Action. (Sep 11, 1950) The Case of Lupo the Wolf.[↩]

- St Louis Post Dispatch (Feb 21, 1938) 3A[↩]

- Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 50[↩]