TABLE OF CONTENTS

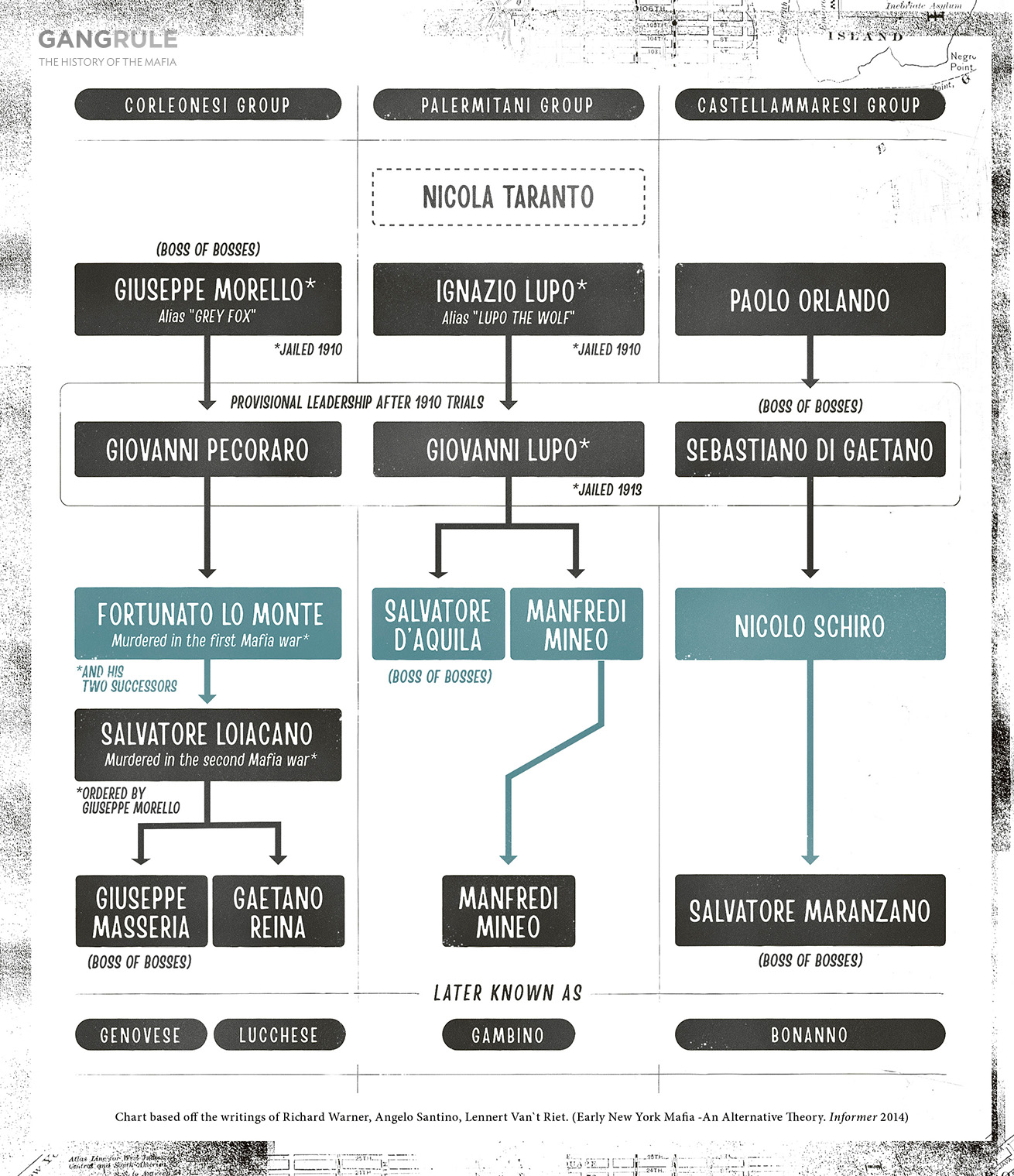

The imprisonment of Lupo and Morello left the US Mafia and two of its families without effective leadership. It is theorized that a short period of provisional governance followed with Sebastiano Di Gaetano of the Brooklyn Castellammaresi acting as an interim capo dei capi (boss of bosses).1 After various legal attempts to secure the release of Lupo and Morello failed, and with Lupo’s brother facing jail for obstruction of justice,2) new family heads were chosen, and the Mafia’s General Assembly elected Salvatore “Toto” D’Aquila as the new capo dei capi of the “Onorata Societa” (Honored Society).3

In 1912, informant Salvatore Clemente revealed to the Secret Service there were actually four Mafia families operating in New York. He explained that “…when a new member is proposed for any one of the four gangs, it is always bought up before the four gangs,” a custom that continued into the modern era. He later named the gangs:4

- The Harlem Lo Monte Gang

Previously run by Giuseppe Morello. The Corleonesi group was now headed by Fortunato Lo Monte. Lo Monte owned a wholesale feed and grain business at 2013 First Avenue and was a business associate of Giosue Gallucci, who controlled gambling and vice in East Harlem.5 (Later divided into the Genovese and Lucchese Families.) - The Harlem D’Aquila Gang

The Palermitani group was commanded by the new overall leader of the US Mafia, Salvatore D’Aquila. Those who knew him described D’Aquila as “a skilful man but his true power lay in his cruelty.”6 A Secret Service agent later described the gang as a “new faction” that grew in popularity and strength.7 (Later known as the Gambino Family.) - The Brooklyn Manfredi Gang

Led by Palermitano Manfredi Mineo who had recently arrived in the US, smuggling printing plates from Palermo. Shortly after his arrival he was questioned by the Secret Service after visiting known counterfeiters.8 - The Brooklyn Nicolo Schiro Gang

Nicolo Schiro became leader of the Williamsburg Castellammaresi group, formerly headed by interim capo dei capi Sebastiano Di Gaetano. Schiro was a cousin to Paolo Orlando, who had been accused by an anonymous informant of instigating the Petrosino murder.9 (Later known as the Bonanno Family.)

The Secret Service had observed bosses Lo Monte and Mineo traveling together in the city and soon learned that the New York families were working together — except for Salvatore D’Aquila, who was “opposed to the other three gangs.”10 The hostilities led to what some researchers have branded as “The First Mafia War.” While the reasons for D’Aquila’s hostility towards the other families can only be speculated, the feud lasted for over two years and resulted in the deaths of rival boss Fortunato Lo Monte and his successors and left D’Aquila with the “absolute predominance in the district around 106th Street.”11

Newspapers at the time misreported some of the killings as revenge for the Barrel Murder or confused them with separate feuds in Harlem, including one that centered around Giosue Gallucci, a political power in the Italian underworld. 12

Joseph DeMarco was a Harlem gangster with known connections in the gambling world. Described in records as 5 1/2 ft, medium build, very dark complexion, “wears a blue suit with a scarf pin made of a sapphire surrounded with diamonds”. He was originally an ally of the Morello group, shown when he offered to help Nick Terranova secure Giuseppe Morello’s release from prison. Fortunato Lomonte and Nick Terranova also helped DeMarco to plan his girlfriend’s murder in July, 1912. They planned to use a car supplied by Charles Pandolfi, an associate whose car was used in the killing of Barnet Baff.13

For some unknown reason, DeMarco’s relationship with the Morello gang faded. He attempted to kill Nick Terranova in Harlem, but his effort failed. Two separate attempts were then made on his own life: he had been walking past 112th St and First Avenue in April 1913, when he was shot in the neck from behind a fence. DeMarco almost died from his wounds but surgeons in Harlem Hospital were able to save his life. The second attempt, in July 1914, was made when he was being shaved in a barber on E106th near 3rd Av, when two men fired at him with sawn off shotguns. More than a dozen slugs entered his body, but he later recovered. 14

DeMarco left his family in Harlem and moved downtown. He opened a restaurant at 163 W 49th Street, and later opened several gambling rooms in Mulberry Street and one located at 54 James Street. He began to lead a double life when he married Anna Maria Landri who lived above his Mulberry Street restaurant, failing to tell her about his current wife in Harlem.15

On June 24th 1916, a meeting took place at Coney Island between the Morello gang and a Brooklyn based Camorra gang. The Camorra group was a loose combination of two Neapolitan groups based in Navy Street and in Coney Island’s Santa Lucia Restaurant at Surf Avenue and the Oceanic Walk. They had previously worked with the Morellos when they assasinated Giosue Gallucci in 1915 to take control of his criminal empire. The idea of the meeting was to discuss the expansion of gambling dens in lower Manhattan. 16

Nick Terranova and Steve LaSalle explained that Joe DeMarco would have to be killed before they could expand in the area. The Brooklyn gang also had an interest in killing him as he had recently taken over one their games on Mulberry Street. On July 20th 1916, Navy Street gunmen made their way to a saloon on Elizabeth Street to await their signal to move. At around five o’clock, they were notified that DeMarco had arrived at James Street. Nick Sassi, an employee of DeMarco, let the gunmen inside. DeMarco sat playing cards with several other men with numerous spectators watching the game. After DeMarco was killed the gunmen made their escape through a bedroom window. 17

Following Gallucci’s death, control of his Harlem policy game had passed to Thomas Lo Monte, brother of the murdered Morello boss Fortunato Lo Monte.18 The game later passed to Pellegrino Morano, leader of the Coney Island group, under the agreement that he would pay the Morellos $25 a week for the privilege. Morano soon stopped payment after running the game at a sizable loss.19

Charles Ubriaco, a rich gold-toothed Calabrian associate of the Morellos, traveled to Brooklyn and tried to reason with Morano, but the Coney Island leader refused any further payment. After the Morellos revoked Morano’s control of the game, the Camorra boss began to plot his revenge and called for the murder of the Morello leadership.20

During a series of conferences held between the two Camorra gangs, they plotted to kill six key Morello members and take control of their gambling, artichoke, ice and coal rackets. Their chosen victims were Giuseppe Morello’s younger half-brothers Nicola, Vincenzo and Ciro Terranova; Charles Ubriaco and Stefano LaSalle, who had both previously run the policy game; and Giuseppe Verrazano, who controlled the late Joe Demarco’s gambling den on James Street.21 One Camorra member believed that killing the Morellos would be so profitable that “everyone would be wearing diamond rings.”22

In September 1916, the Camorra attempted to lure the six Morello men to a meeting at the Navy Street cafe, but only Nicola Terranova and Charles Ubriaco made the journey from Harlem. Both were ambushed and killed, shot from close range at the junction of Johnson Street and Hudson Avenue.23

Four weeks later, Navy Street gunmen entered the Italian Gardens restaurant on Manhattan’s Broome Street, formerly a part of the Occidental Hotel which Tammany leader Tim Sullivan made his headquarters. Late-night diners, including a group of local vaudeville actors, hid behind tables while the Camorra gunmen fired into the restaurant, killing Giuseppe “Big Man” Verrazano.24 The Morellos soon withdrew their downtown operations and, within a week, the Navy Street gang opened a gambling den in Hester Street.25

The Camorra never saw the riches anticipated with the takeover of Morello rackets. They faced tough negotiations with the city’s gambling and policy bosses before an acceptable level of “tax” was agreed upon, and the tribute they received from artichoke dealers was half of their initial demand.26

Fearing revenge from the Morellos, the Camorra leaders tried numerous schemes to murder the three remaining men on their hit list. They tried persuading Morello associate “Louis the Wop” to betray his bosses and poison their food, but his allegiance was too strong and he exposed the plan.27 They also attempted to persuade two Harlem locals to shoot Ciro and Vincenzo Terranova while they made ice deliveries in the area, but the locals declined to help and were consequently shot by the Camorra.28

Things began to unravel for the Camorra in early 1917. Navy Street boss Alessandro Vollero was hospitalized in January after the Morellos shot him just a short distance from where Nicola Terranova had been slain.29 In February, the police raided policy dens all over the city, including the Navy Street cafe where a stash of policy slips was discovered.30 A month later, Navy Street gunman Ralph Daniello was placed on trial for robbing a young drug dealer working for the group. The trial exposed details of the gang’s cocaine distribution business.31 A week later, the Navy Street cafe was raided, and proprietor Leopoldo Lauritano was convicted of possession of dangerous weapons.32

Daniello was arrested again in November 1917 in connection with a drug-related murder. He quickly admitted his involvement with the Camorra and furnished the district attorney details of twenty-three gang murders stretching back over the last two and half years. Daniello’s confession helped clear up crimes that had puzzled the NYPD and quickly led to a series of arrests.33 The resulting investigations revealed bribes paid by the Camorra to NYPD detectives, including Michael Mealli, who had been part of the Italian Squad and worked with Joe Petrosino. Mealli was demoted and eventually retired on account of physical disability in 1918.34

Daniello’s detailed confessions, along with testimony from other gunmen, resulted in convictions that decimated the Brooklyn Camorra gangs. Several members received the death penalty, and the gang’s leadership received heavy sentences. The Morellos managed to escape sentencing when Ciro Terranova, tried for his involvement in the killing of gambler Joe Demarco, was acquitted in June 1918.35

- Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. 38[↩]

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter referred to as NARA), RG 87, Daily Reports of Agents, (hereafter referred to as DRA). New York. Vols.34-36 (Feb 25, 1912)

NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vols.37-39 (Feb 6, 1913[↩] - Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 38

‘La Cosa Nostra – Anti-Racketeering – Conspiracy’ – FBI 7/1/1963. 33 [↩] - Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 36

NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vols.34-36 (Feb 25, 1912)

NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vols.40-42 (Nov 10, 1913)

Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 59[↩] - The Pittsburgh Press (Dec 12, 1915) Magazine Section

The Evening News-Wilkes-Barre, Pen (Oct 14, 1915) 2[↩] - Translation of Nicola Gentile article by Felice Chilanti in Paese Sera. Rome. September 14, 1963.[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol.80 (Oct 5, 1922) [↩]

- The Morning Call (Jul 12, 1911) 9

NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol. 32 (July 1911) [↩] - Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 55

Petacco, Arrigo (1974) Joe Petrosino. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. 169[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vols.37-39 (Apr 22, 1913)

NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vols.40-42 (Nov 10, 1913) [↩] - Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 56-62[↩]

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Nov 25, 1913) 9

The Pittsburgh Press (Dec 12, 1915) Magazine Section[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol. 36 (Jul 18, Aug 20 1912)

New York Tribune. Oct 28, 1919. p.22[↩] - The People of the State of New York against Angelo Giordano. 633 Part 1.

New York Herald. (July 21, 1916)

New York Evening World. (April 14, 1913) [↩] - New York Tribune (July 23 1916)

Manhattan Marriage Certificate #28674[↩] - The People of the State of New York against Angelo Giordano, 231 New York 633 pt. 1.

Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 112[↩] - Giordano transcript New York 633 pt. 1.

Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 112[↩] - Giordano transcript. exhibit #1. 186-187

Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. 60[↩] - Giordano transcript. exhibit #1. 186-187 [↩]

- Giordano transcript. exhibit #1. 186-187

The Sun. New York (Aug 26, 1912)

The People of the State of New York against Alessandrio Vollero, Case on Appeal, 226 New York 587 pt. 1. (hereafter Vollero transcript) List of conferences. [↩] - Vollero transcript. Opening address. 50[↩]

- Vollero transcript. Opening address. 121[↩]

- Brooklyn Times Union (Sep 8, 1916) 5[↩]

- The Evening World (Oct 6, 1916) 9

Buffalo Evening News (Dec 20, 1922) 1

The New York Times (Oct 4, 1903) 2 [↩] - Smashing the Gangs of Little Italy. Master Detective. Oct 1995. 33[↩]

- Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. 122

Smashing the Gangs of Little Italy. Master Detective. Oct 1995. 33

Vollero transcript. 73[↩] - Vollero transcript. 200

Smashing the Gangs of Little Italy. Master Detective. Oct 1995. 34[↩] - People of the State of New York v Charles Rossi Chiafalo, Peter Bianco and Sam Sacco. (1918) # 2396. Criminal Trial Transcripts (1883–1927), Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice/CUNY[↩]

- Vollero transcript. 86, 428

Brooklyn Times Union (Jan 26, 1917) 7[↩] - The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Feb 13, 1917) 18 [↩]

- The Brooklyn Citizen (Apr 21, 1917) 12 [↩]

- Brooklyn Times Union (Apr 28, 1917) 12 (May 7, 1917) 4[↩]

- New York Tribune (Nov 28, 1917) 16

The Topeka State Journal (Nov 30, 1917)

Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. 107[↩] - Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. 124.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Dec 18, 1918) 1[↩] - The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Jun 7, 1918) 12[↩]