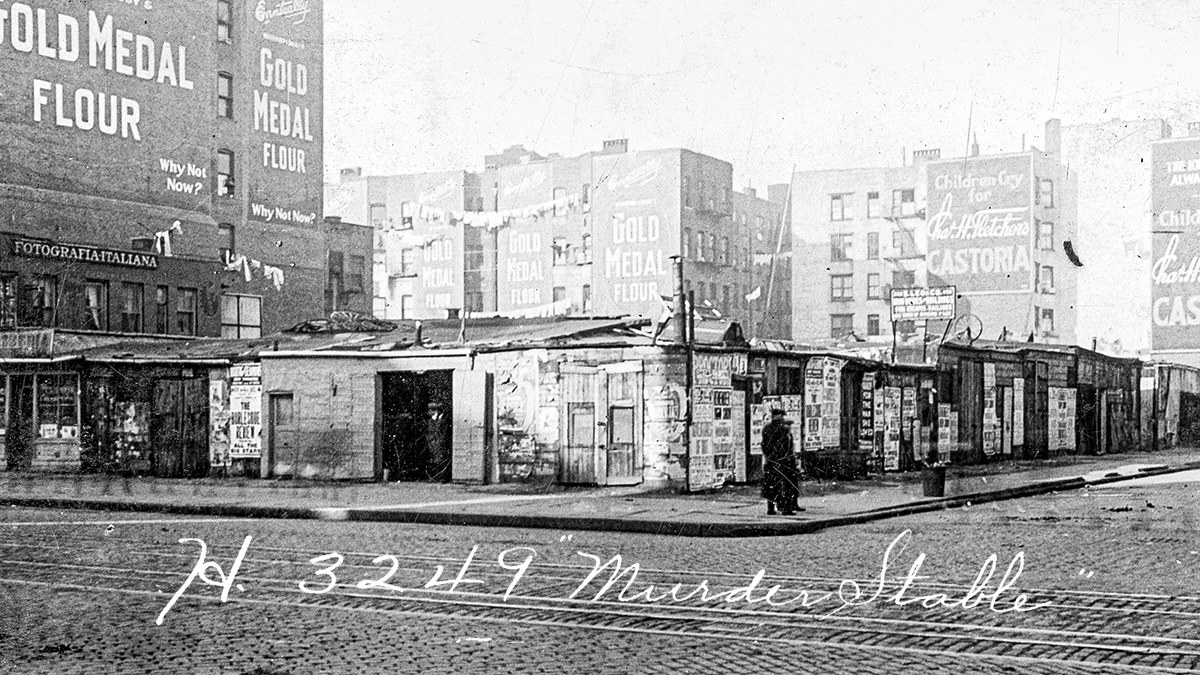

A collection of run-down timber frame structures once stood at the corner of New York’s First Avenue and East 108th Street. A maze built from sheet iron, packing boxes and discarded house wreckage. The land housed a boarding stable encircled by a combination of junk shops and wagon storage. Following a series of killings in the location, they became collectively known as the “Murder Stables”. 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

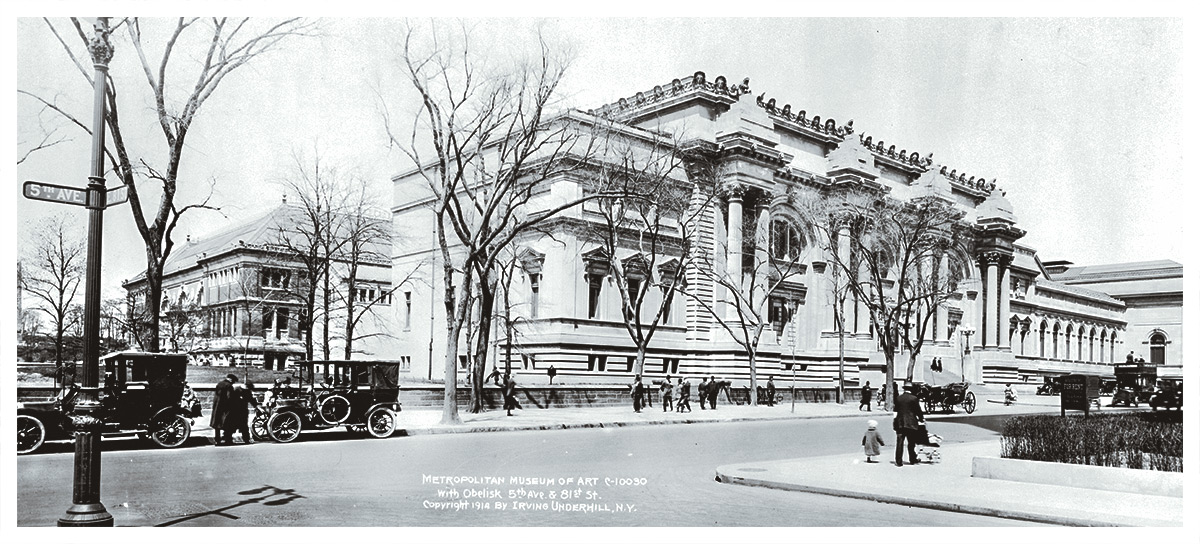

In 1898, the Cullen & Dwyer stone and granite company occupied the land. Headed by quarry owners, John Cullen and Thomas Dwyer, the business was involved with numerous projects in New York City, including the construction of a new entrance to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The company erected buildings and stables in the yard to accommodate its rapid growth. As a personal project, an employee secured part of the land to construct a 51ft motorboat which he later launched in the Harlem River.2

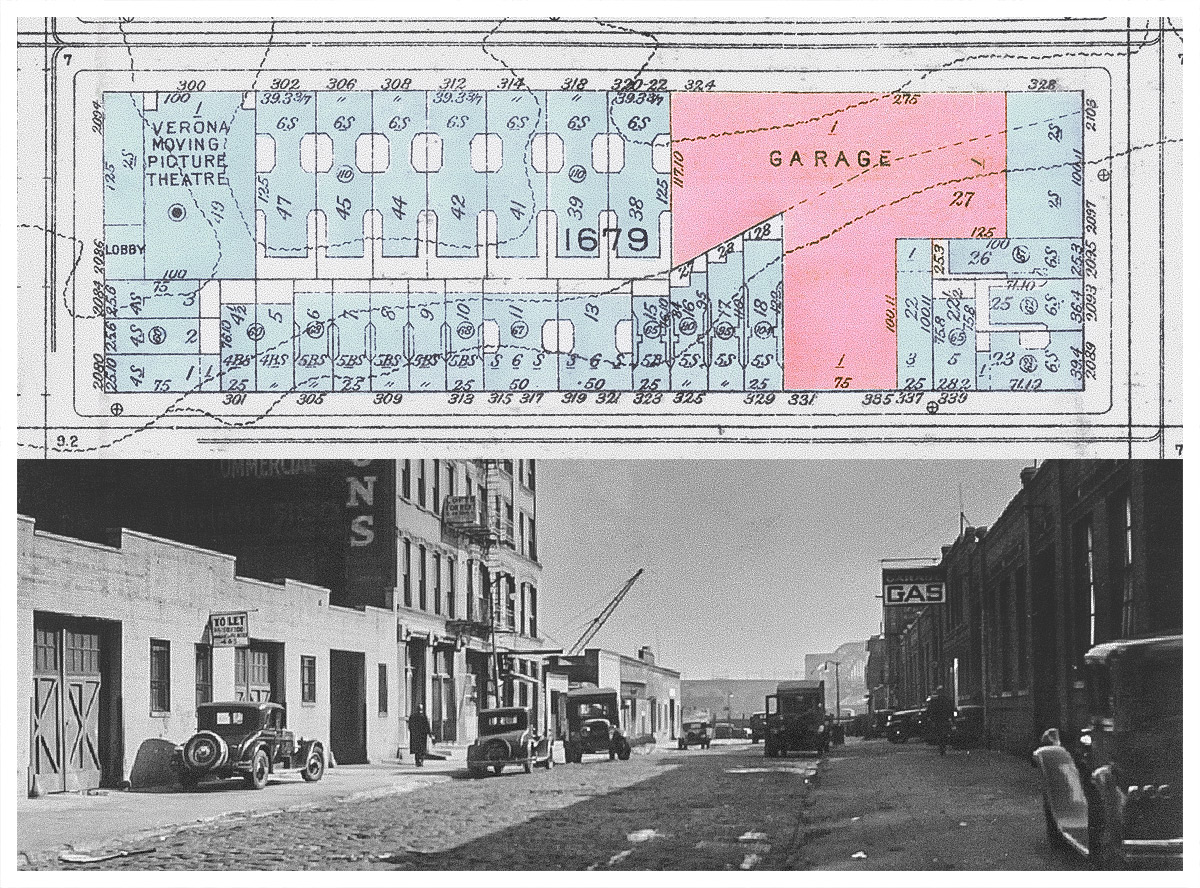

In 1901, Thomas Dwyer left the company and the stone works were later shut down. John Cullen kept Cullen & Dwyer operational as contracting business, working from an office on the east side of the block. Cullen later purchased the land and passed ownership to his daughters. A 1918 study of their holding showed it yielded little income – “the low frame buildings are unsightly and dangerous and should be raised. They are a menace to the new law tenements to the west of them.” The estimated value of the real estate barely changed over a ten-year period.3

An Austrian governess was attacked in June 1905 while making her way back to her employer’s residence. She had stopped on East 108th Street to ask for directions when she was dragged inside the stables and robbed of her diamond jewelry. Her screams alerted the police who arrested Antonio Letaso, a local 22-year-old driver. They also detained the stable’s nightwatchman as a witness. Letaso received a nine-year sentence in Sing Sing prison for the attack.4

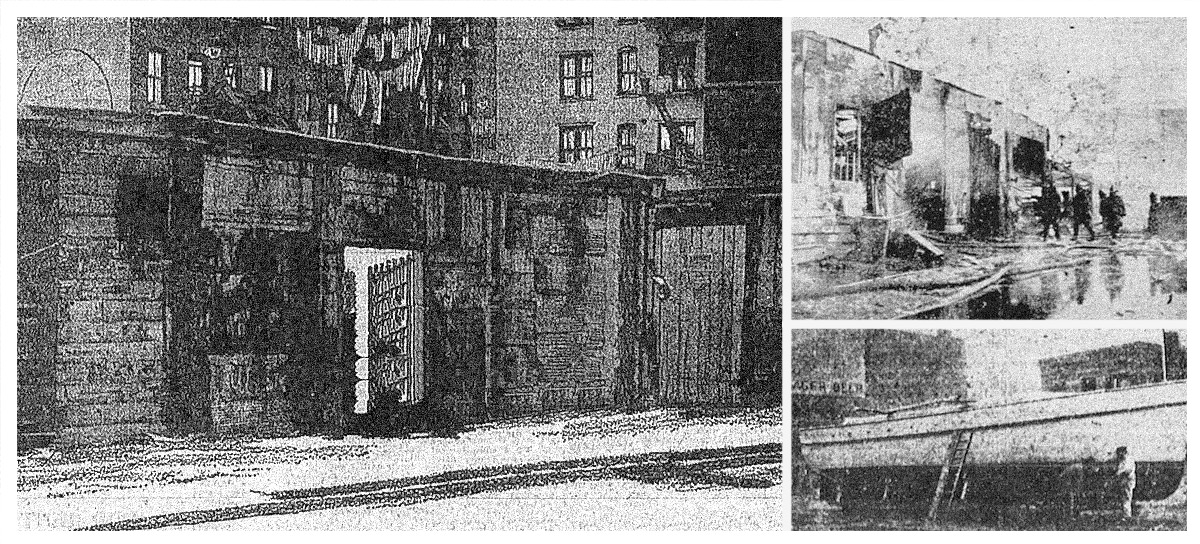

In September the entire structure was burnt overnight. Stable manager, Joseph Barella, lost over ten horses in the blaze. Occupants in neighboring buildings were forced to jump to safety. The total damage was estimated to be around $5,000.5

In 1906, the stables were destroyed in another fire that started in a rag shop belonging to blacksmith Nunzio Squillante. The flames quickly spread from East 108th down to East 107th Street. Several firemen were injured trying to save the horses from the blaze. Once again, the adjacent residents were forced to flee and some were injured by furniture being urgently tossed from apartment windows. This time the losses were estimated at around $10,000.6

The hazardous mix of timber shacks, rag storage and blacksmiths were a clear danger. In April 1909, yet another fire damaged the property. A junk shop and six adjoining rag-filled shacks caught fire. Swarms of rats escaped into the neighborhood after the firemen tore up flooring to free their Battalion Chief who had become trapped. The owner of the destroyed junk shop was Pasqua Musone7, a stocky Neapolitan woman who would become a notorious figure in East Harlem.

Pasqua Musone made the journey to the US in 1892 at the age of 36. She likely traveled from the town of Marcianise, Campania, twenty miles north of Naples.8 In 1895, her daughter Concetta married Michelle Lasco, also from Marcianise. He ran a blacksmith shop on East 107th Street next to the Cullen & Dwyer stone yard.9 By 1904, Pasqua had started to build a property portfolio. Together with her son-in-law, she purchased property on First Avenue consisting of a one-story timber frame building and the adjacent vacant lot.10

Her purchases were conveniently located just south of her home at 345 East 109th Street. She lived with her second husband Pietro Spinelli who worked at a fish store located on the family’s new property. Her children, Tomasso and Nicolina Lener, were born to her first husband Domenico Lener who had passed away in Italy. Tomasso left home in 1907 after he was married at St. Lucy’s Church on East 104th Street.11

By April 1909, Pasqua was the owner the junk shops connected to the East 108th Street stables. In June she spent $1,000 extending and remodeling an adjacent property at 2097 First Avenue. It was an old stone structure housing the 300 seat Elena Cinematograph theatre with the offices of Cullen & Dwyer located on the second floor. Pasqua and her husband were both involved in the management of the theatre and by August the family had relocated to accommodation above the auditorium.12

Pasqua earnt the sobriquet of “The Hetty Green of Harlem” for her wealth and thrifty business manner (The real Hetty Green was a rich, miserly businesswoman of the era). She was said to walk the same route each day making personal inspections of her properties, trusting their management to no one else.13

On August 24th, while the theatre improvements were being completed, Pasqua’s daughter Nicolina married Gaetano Napolitano. He ran a butcher shop in the Bronx having arrived from Campania in 1897. The pair were wed in a civil ceremony in the City Hall witnessed by Nicolina’s stepfather. Their choice of a civil ceremony upset Pasqua. She prevented the pair from living together until they were wed in a religious ceremony and Napolitano could prove his financial worth.14

Two days after the wedding Pasqua transferred ownership of her First Avenue real estate to her daughter as a gift. However, Napolitano ended the relationship. The press speculated his failure to secure a dowry and quarrels with his new mother-in-law had caused him to leave. Eight months later, census records listed him as being single.15

There was yet another fire on January 30th 1910, causing an estimated $1,500 worth of damage to the central stables. The loss was reported under Pasqua’s name, revealing her ownership, or at least part-ownership, of the livery business as well the junk shops. Her theatre was also facing problems. Although the venue had been granted an entertainment license it was referred to the authorities for breaching fire regulations. Just months later, a major fire was narrowly averted after police spotted two men fleeing from the building. The stage had been doused in kerosene but the flames were quickly extinguished before any serious damage was done.16

A week later, the theatre was hosting a vaudeville show for around two-hundred patrons when a small explosive device was tossed through a window. Panicked cries of “Black Hand!” caused the excited crowd to rush for the exits, and left several people seriously injured in the resulting stampede. The police dismissed the incident as a practical joke as the device was similar those thrown during Italian street celebrations.17 Pasqua continued with her property investments and began to purchase plots outside of Harlem. In October, she acquired land located next to an old marble quarry in the town of Eastchester.18

Pasqua had more troubles in July 1911. A court judgement had been brought against her ordering one of her properties to be vacated. Weeks later, her First Avenue fish store where her husband Pietro worked was auctioned under foreclosure. The judgement showed that her debt was owned along with Aniello Prisco, a notorious and violent criminal.19

Prisco lived at 2133 First Avenue on the block adjacent to the fish store. He was nicknamed “Zoppo” (lame) after a gunfight with “Scar-faced Charlie” Pandolfi shattered his leg and left him with a permanent limp. His frequent terrorism of the neighborhood led to his nickname becoming a synonym for blackmail or brutal crimes in East Harlem. A week after his court judgement with Pasqua he was caught carrying a concealed weapon and sentenced to six months imprisonment.20

Following the troubles with the theatre and the closure of the fish store, the family moved back to East 109th Street. Pasqua’s daughter, Nicolina, had previously been romantically involved with the criminal Frank “Tough Chick” Monaco. Born in the US, his parents had arrived from Campania in the 1880s and settled in Harlem close to the stables. He was described as the last of a triumvirate that held the district in terror and was said to have been a “former Lieutenant of Paul Kelly in Harlem.” According to the police, the pair would frequently quarrel. Nicolina had lodged complaints against Monaco on several occasions, but the police took no action as they considered it a domestic problem.21

On October 6th, Monaco, who had recently completed his parole from Elmira reformatory, killed an acquaintance of Nicolina. He chased Michael Barbaro, a notorious horse thief, after spotting him loitering in his stables. Later that day he shot Barbaro three times after meeting him in a First Avenue saloon. Monaco was arrested and held on $5,000 bail.22

After posting bail, Monaco went to Nicolina’s home on East 109th where he was killed in a brutal and sustained attack that left him with eighteen stab wounds. Nicolina walked to the East 104th police station and calmly confessed to the murder. The police escorted her back to her residence which was found in a wild state of disorder with Monaco’s body lying on the floor. She was charged with homicide and remanded in custody by the coroner.23

Nicolina’s story was reported in the following day’s headlines. She claimed that several months back she had been assaulted by Monaco. He had taken her to Westchester to help to locate her estranged husband but had instead held her captive in a remote building for several days. Nicolina stated that she managed to escape and made her way back to Harlem. She added that she had killed Monaco for attempting to steal her family’s savings.24

The authorities were doubtful of her story. After performing the autopsy at Bellevue Hospital the coroner’s physician said,

“I cannot see how it was possible for this girl to find the strength to make the prolonged fight evidenced by the man’s condition … in my opinion, no woman of her slight strength could carry through such a ferocious attack.”

An inspection of her clothing revealed they were only lightly marked but somebody involved in such a fight should have been heavily blood stained.25 She also claimed that she had required help locating her estranged husband in Westchester, but his family address was recorded on her marriage certificate.

There were also problems with her statement that she acted alone. Monaco’s body was found pinned under a 400lb safe that she could not have moved by herself. A witness who passed the apartment before the murder recalled seeing four hats placed on a table, but they had all later vanished. The police thought Nicolina was shielding the real killers. They suspected she had lured Monaco to her apartment where he was murdered in revenge for shooting Barbaro the horse thief. Despite their concerns, the coroner’s court acquitted Nicolina and she returned home.26

The policeman who had taken Nicolina’s statement re-told the story in 1951. Describing Nicolina as a pleasant and mild-mannered daughter of fish-store owner, he claimed she had lured Monaco to her home using “cooing words” where he was killed for attempting to extort her mother.27

Pasqua and her family moved to 335 East 108th Street directly across from the stable’s entrance. Five relatives kept the apartment under close guard. They received letters warning that Monaco’s murder would be avenged and threatened them with death if they dared to venture outside. Various stables with connections to Pasqua were set ablaze. She had wanted to attend Harlem’s thanksgiving celebrations, but friends advised her it would be too dangerous. Her isolation began to make her paranoid and she would often wake at night thinking someone had broken into her home.28

In December 1911, the Secret Service were informed that the Terranova brothers had opened a blacksmith shop “in a shanty in 107th Street near 1st Avenue.” 29 It was most likely located in the same yard as Pasqua’s stables. The Terranova brothers were Nicola, Vincent and Ciro, half-brothers of Giuseppe Morello the recently incarcerated ‘boss-of-bosses’ of the US Mafia.

Pasqua felt that her death was inevitable and told her daughter they would both eventually be killed. On March 9th, 1912, she transferred ownership of her land in Eastchester to her son Tomasso.30 Eleven days later she ventured outdoors. She made her way over to the stables, reassured by the knowledge that her husband was already on the premises. Nicolina was keeping watch from her apartment window when she spotted two men following her mother. It was too late to warn her, they shot Pasqua killing her instantly and made their escape towards Second Avenue.31

A large crowd of excited locals tried to force their way into the stables before being dispersed by the police. Nicolina and her stepfather were taken to the East 104th police station. A distraught Nicolina described the two killers to the police who recognized them as being close associates of the late Frank Monaco. Twenty-five detectives were sent out in search of the killers.32

Two days later the police arrested Luigi Lazzazara, a middle-aged horse dealer and part-owner of the stables. Nicolina had implicated him in the murder during her affidavit and other witnesses had seen him open the stable’s doors to aid the killer’s escape. However, he was eventually released due to lack of evidence.33 He was later placed on trial for horse theft and his stables put under surveillance on the suspicion it was sheltering stolen horses.34

Horse theft had become so widespread that insurance companies stopped offering policies. One insurer commented “I came to the conclusion that stealing horses had become an organized institution rather than a private industry.” It was estimated that five horses and wagons, each worth around $800, were stolen every day in New York. The horses were disguised by trimming their manes and tails with any distinctive marks concealed with dye. Similarly, wagons were chopped, reconfigured and repainted.35 During a meeting of the Horse Owners’ Protective Association in 1913, the organizer celebrated the decline of horse theft in the city and named the “Lazzazarro gang” as having been key operator.36

The next suspect to be detained was Aniello Prisco who had been recently released from prison for a concealed weapon charge. He was arrested on June 18th 1912, after the police recognized him from Nicolina’s description of her mother’s killers. He was indicted for homicide and tried by a Grand Jury. However, he was dismissed in September after several key witnesses failed to appear; including Nicolina who had fled to Italy for her safety.37

Pasqua’s murder remained unsolved. Joe Valachi, who grew up on East 108th Street and was part of the crowd that pushed into the stables, recalled the events in his 1964 memoirs. He claimed that Pasqua had killed Monaco for assaulting her daughter and that a Monaco associate took revenge after being released from prison . Valachi’s version of events ties with the facts that Prisco had been in prison at the time of Monaco’s killing and was released shortly before Pasqua’s murder.38

Later that year, Harlem gangster Antonio “Sharkey” Zaracca was involved in shootout with man known as “Coney Island” Joe. He went into hiding but was tracked down on September 2nd, and killed in Café Degli on East 109th Street. Coney Island Joe and his fellow gunmen managed to escape the area before the police arrived.39 Prisco was arrested the following month on East 108th Street as a suspect. He was arraigned before the coroner but, once again, discharged due to lack of evidence.40

The Deputy Police Commissioner had received new information connecting Prisco to Pasqua’s killing. Anonymous tip-offs declared that he had been hired for the job by Giosue Gallucci, a powerful criminal leader with strong political connections. The informants claimed that Gallucci had been angered by Pasqua’s readiness to pass information to the police since the death of Monaco.41

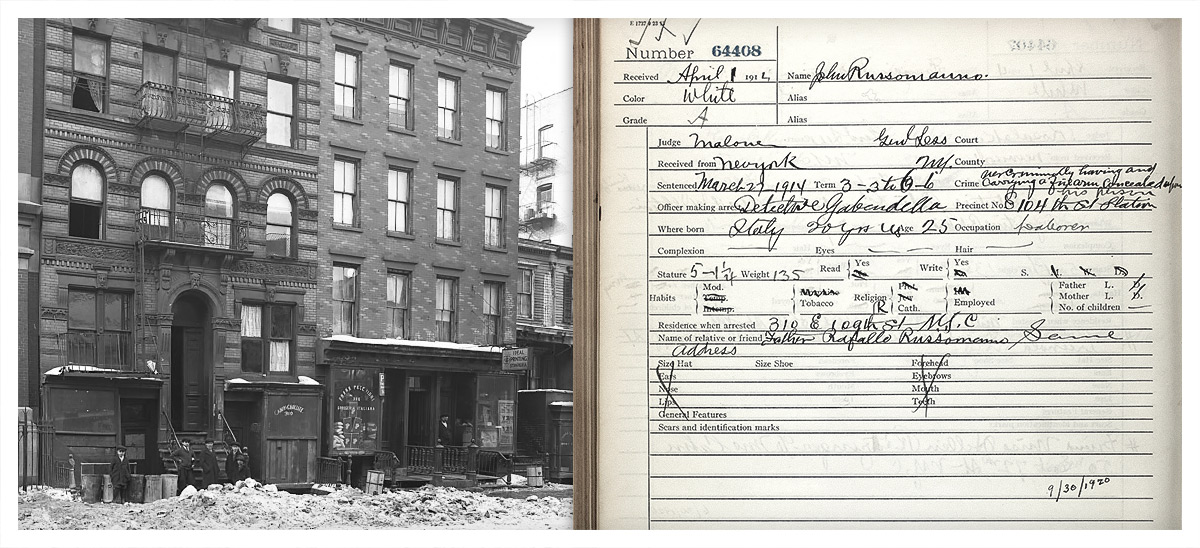

At around midnight on December 15th, Prisco walked into Gallucci’s bakery on East 109th Street. Shortly after his arrival he was fatally wounded after being shot by Gallucci’s nephew John Russomano. On his lawyer’s advice, Gallucci took his nephew to the coroner’s office where he casually confessed to killing Prisco. He claimed the shooting was done in self-defense after Prisco had attempted to rob his uncle at gun point. Russomano was charged with homicide and his bail was set at $5,000, which was speedily furnished by a Harlem real estate dealer. Five days later the killing was deemed justifiable homicide and Russomano was discharged.42

The District Attorney and the press told a different version of events leading to Prisco’s death. They claimed that Prisco had gone to Gallucci with demands for more money: “You have not been giving me anything of what you have been getting for some time, I am down and out, I am now a bum”, and that the pair had arranged to reconvene the following day at a shop belonging to Nicola Del Gaudio. However, Gallucci feigned illness and sent one of his men, Antonio Vivolo, to a theatre on First Avenue to locate Prisco with instructions to meet at Gallucci’s bakery where Prisco was then shot.43

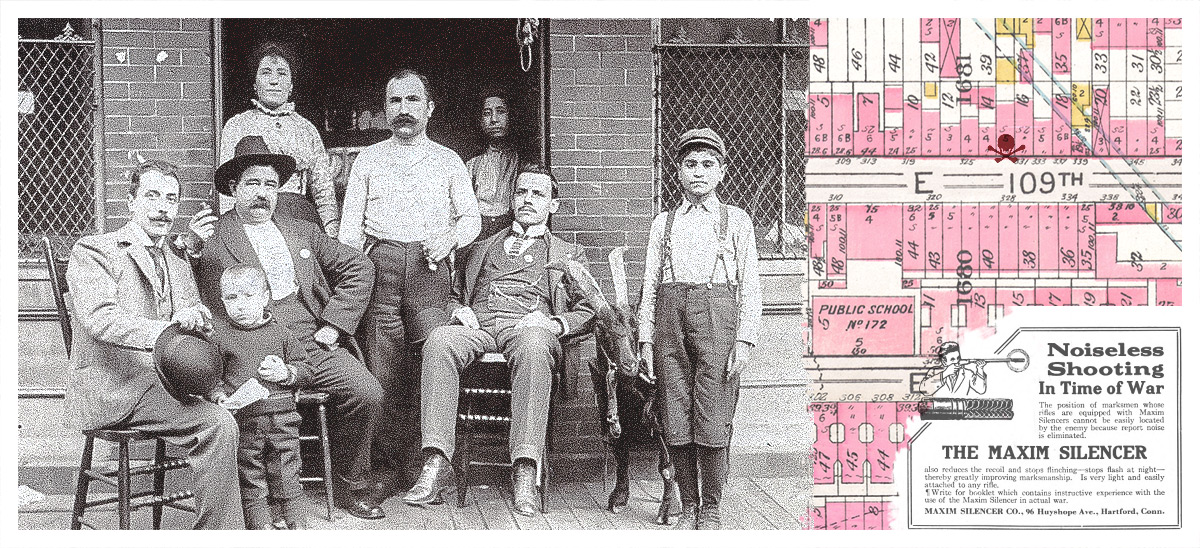

Two months after Prisco’s assassination his allies retaliated. On February 18th 1913, Gallucci, Russomano, and Vivolo were ambushed outside of 329 East 109th Street. They were shot with a rifle equipped with a Maxim Silencer, a new device that had been developed in Connecticut. Vivolo died instantly, Russomano was wounded and sent to Bellevue Hospital. Gallucci managed to escape serious injury when a bullet passed through his coat sleeve.44

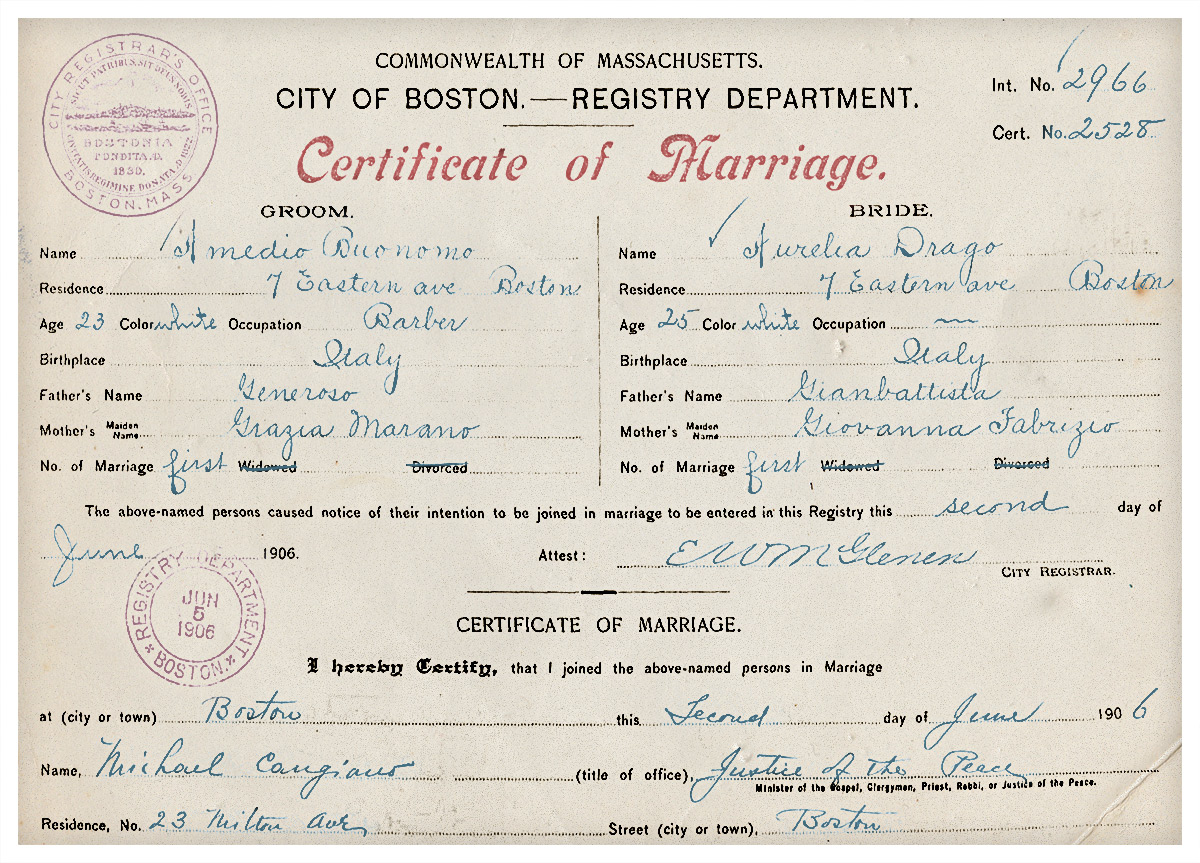

Gallucci exacted revenge on those connected with the attack. Charles Marone, suspected of being one of the gunmen, was later killed in a saloon. Nicola Del Gaudio, whose name was linked to the attack, travelled to Naples and was later shot down after returning and demanding more money from Gallucci. The first to be killed was Amedio Buonomo, an associate of Prisco. He was described as a man of importance in Harlem’s Little Italy and a “leader of a coterie of men”.45

and son Luca Gallucci (far right). E 109th St (c.1900)

Little is known about Buonomo. He was born in 1884, to Generoso Buonomo and Grazia Morano. In 1895 he travelled to Boston from Pratola Serra, Campania.46 He had appeared briefly in the papers two months after Monaco’s murder in 1911, when he was shot in a fight in Thomas Jefferson Park. Twenty men, including some that had travelled from Philadelphia, had agreed to meet in the park for a pre-arranged fight. Witnesses said the battle was a vendetta, while others said it was a fight over a girl. One of those injured was a notorious character known as “Tough Louie” Brindisi who used to run a saloon on Water Street in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Buonomo was taken to the hospital and gave his address as Westchester Avenue, a remote and undeveloped part of the Bronx.47

Following Gallucci’s murder of Prisco, Buonomo had purchased a chainmail vest for his personal protection. On April 5th 1913, he made the fatal mistake of leaving home without his armor. He was gunned down on East 113th Street close to Thomas Jefferson Park. Five days later, his impressive funeral procession made its way from his home on Madison Avenue. Headed by a 42-piece band, it was formed of over hundred carriages and guarded by a similar number of detectives. The police arrested “Diamond Joe” Viserti as a suspect for his murder. Viserti was a friend of the Terranova brothers who would later make his fortune in bootlegging. He was eventually released due to a lack of evidence. (Viserti used to live at 335 East 108th Street, the same building as Pasqua. His marriage in 1911 was witnessed by Antonetta Spinelli, likely connected to Pasqua.) 48

The police stated there had been six “mysterious street murders” and ten shootings since the attack on Gallucci. The press referred to them as a war between the “Russomanno-Gallucci” and “Prisco-Buonomo factions”. The tit-for-tat conflict continued when Joe DeMarco was wounded on April 14th. DeMarco was an ally of the Terranova brothers and ran the grain and feed store attached to the stables. Two days later, Pietro Martino was shot while entering his home on East 117th Street. He had been suspected of hiring the men who killed Buonomo. Two weeks later, Gallucci’s faction was credited with the shooting of three people outside the Elena theatre once managed by Pasqua Musone.49

Prisco’s death triggered a wide-ranging investigation that would eventually ensnare Gallucci. NY District Attorney Whitman had setup a homicide bureau to investigate murders in the city, interviewing witnesses and gathering evidence firsthand: “Some of the more important convictions we have been able to obtain have been the direct result of either myself or my assistants being promptly on the scene of a crime.”50 Assistant District Attorney Murphy was working at the bureau when he opened an investigation in Prisco’s death. It would later lead to the discovery of a city-wide vice ring “responsible for about one murder a week”.51

Both factions of the war had connections to the city’s vice trade. Buonomo’s brother, “Chicago Joe”, was part of a “white slave” gang. He was sentenced to death in 1912 for killing a woman he had trafficked from New York to Chicago where he was said to be a friend of vice-king Jim Colosimo of the Chicago mob. Gallucci was also linked the trade and referred to as “King of the White Slavers”, he ran a brothel close to his bakery on East 109th Street.52

In July, Assistant D.A. Murphy decided the most successful way to break up the vice ring would be to arrest the leaders for gambling violations. After weeks of planning, twenty-five detectives raided policy shops in Harlem and Mulberry Street. Among the forty arrests were Gallucci and his nephew Russomano, who were both held for carrying concealed weapons. Gallucci was released on $10,000 bail while Russomano was sentenced to three to six years at Sing Sing prison.53

The District Attorney’s office received several letters of congratulations. One letter signed by Harlem business owners stated:

“On last Saturday a big number of the worst men belong to the worst gang of the world were arrested. The head man of this gang that was also arrested the name is Gesule Lugariello, alias Gallucci. He is the head man Italian Lottery. He is the man who gives the order to his men to kill.”

Another letter confirmed that Gallucci had been responsible for the death of Amedio Buonomo.54

Two years after the death of Pasqua Musone the stables were still managed by her old business partner Luigi Lazzazara. Although he had been arrested in connection with her murder he had managed to escape conviction. He finally met his end on February 19th, 1914. He was making his way past 2106 First Avenue when he was stabbed to death by Angelo Lasco, a brother of Pasqua’s son-in-law. The police found Lasco nearby, drunk and bloodstained. A detective overheard him muttering to himself: “Now, I’ve made as mess of this thing”.55

The war had left Gallucci and his allies with dangerous enemies.

- Andrea Ricci was a partner of Prisco but had been in jail for horse theft at the time of his friend’s murder. He left Harlem and became a leader in the Brooklyn Navy Street gang and was later initiated into the Camorra.56

- John Mancini, who stole horses with Ricci, later became an inducted member of the Coney Island Camorra group.57

- Pellegrino Morano was an uncle of Amedio Buonomo. He lived on East 116th Street and ran a liquor store near to Buonomo’s coffee shop but was forced to leave Harlem. He later led the Camorra group in Coney Island and demanded retaliation against the Terranovas for the murder of his nephew.58

- Alessandro Vollero, a boss in the Navy Street gang, sought retribution for the killing of Nicolo Del Gaudio – a “fellow townsman” from Gragnano, Campania. Another Navy Street leader from Gragnano was Leopoldo Lauritano. He married Del Gaudio’s widow who had sworn a vendetta against her husband’s killers.59

- Andrew Rege, who stole horses with Pasqua’s old business partner Luigi Lazzazara, relocated from Harlem to Brooklyn. He aided the Navy Street gang with the killing of a Gallucci associate.60

113 Navy Street, June 27th, 1916. (1. Andrea Ricci 3. Leo Lauritano 4. Alessandro Vollero)

Gallucci was assassinated in May 1915 in his son’s East 109th Street café. One of the gunmen was Andrea Ricci, Prisco’s old partner and then boss of the Navy Street Gang. Gallucci had been betrayed by his own allies and bodyguards who assisted the Brooklyn gang with its first killing. It was primarily an effort to gain control over his criminal empire, but many those involved also sought revenge for the deaths of their associates. Mafiosi Joe Valachi, later recalled Gallucci’s funeral, describing it as “one of the biggest of all the ones I saw around this time.” The procession was comprised of 150 carriages and the roofs, fire escapes and doorways along its route were packed with curious onlookers.61

Most of the key figures involved in the war were dead or incarcerated. The Brooklyn Camorra, who had worked with the Terranova brothers to assassinate Gallucci, continued the relationship and began work on expanding their gambling operations in the city.

Not all the shootings and murders that occurred in the vicinity of the stables were connected to the hostilities with Gallucci. Giuseppe Gandolfo, who had run a wagon business on the premises since 1910, was wounded in 1914 for reasons unknown.62 Fortunato and Gaetano Lo Monte, who ran the grain and feed store on the corner of premises were both killed in a Mafia war with Toto D’Aquila. Their store then passed to Frank Badolato, who had run the Ignatz Florio Co-operative with Mafioso Giuseppe Morello.63 Ippolito Greco, who ran the stables in 1915, was gunned down outside the premises. He had been connected to the killing of Barnet Baff, a case that spawned the sensational term “Murder Stables” in the headlines. The car used in the killing of Barnet Baff was said to have belonged to “Scar-faced Charlie” Pandolfi, the same man who had shattered Prisco’s leg in a gunfight.64

John Cullen, the owner of the land, later converted the old stables into a garage. He leased the property to John Rumore, a Morello gang associate who ran an undertaker business next to the city block.65

The term “Murder Stables” lingered in the press for decades to come. In 1939, The New York Sun used the term in a light-hearted Saturday quiz, asking its readers to name the location of the infamous shacks.66 The entire city block was demolished and remodeled in 1961 as part of the Franklin Plaza project.67

- Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette. Dec 12, 1915[↩]

- New York Times (NYT). Feb 26, 1898. p.10

Insurance Maps of the City of New York. Bromley, George W. and Bromley, Walter S. Atlas of the City of New York Manhattan Island. Plate 40, Part of Section 6, 1898

New York Tribune. Jul 22, 1900. p.14

The Sun. New York. Mar 26, 1905[↩] - NYT. Oct 17, 1901

New York Tribune. Mar 15, 1910

Block sketches of New York City. Clara Byrnes. New York: Radbridge Co Inc, 144 Pearl St., 1918

New York City Record Office. Annual record of assessed valuation of real estate in the city of New York. New York. (1906-1916) [↩] - Evening Telegram. June 12, 1905. p.2

New York, U.S., Sing Sing Prison Admission Registers, 1865-1939. #55771[↩] - The Boston Globe. Sep 27, 1905

The Sun. New York. Sep 28, 1905[↩] - New York Tribune. Jan 8, 1906

NYT. Jan 8, 1906

The Sun. New York. Jan 8, 1906. p.12[↩] - New York Herald. Apr 26, 1909. p.6

[↩] - Ship: Hindoustan. July 6, 1892. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #14403. (Tomasso Lener)

New York State Population Census, 1905; A.D. 33 E.D. 05; City: Manhattan; County: New York. (345 E 109th) [↩] - New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #17498 (Concetta Lenere)

Trow’s New York City directory, 1897-1898. p 825

The New York Times. Mar 9, 1898. p.10

U.S., Passport Applications. Michele Lasco #74691 1920[↩] - Real estate record and builders’ guide. New York: F. W. Dodge Corp. Vol. 73. March 12,1904. p.567 (2113-2115 First Av.)

(Lasco had previously leased the property for his wagon business in 1899: Trow’s New York City directory, 1899-1900 /Real estate record and builders’ guide. vol.64. 1899. p.893)

(The neighboring land of 2117 First Av. was briefly acquired at some point later. Shown when Pasqua leased the property: Real estate record and builders’ guide. Vol.76. Sept 2, 1905. p. 383) [↩] - New York State Population Census, 1905; A.D. 33 E.D. 05; City: Manhattan; County: New York. (345 E 109th)

Hunt, Thomas, “Spinelli’s killing sparked Murder Stable legends” The American Mafia, mafiahistory.us, last revised 08 Dec 2021.

NYT. Oct 30, 1911. p.20

New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #14403. (Tomasso Lener) [↩] - New York Herald. Apr 26, 1909. p.6

Real estate record and builders’ guide. New York: F. W. Dodge Corp. V. 83 June 19, 1909. p.1250

Block sketches of New York City. Clara Byrnes. New York: Radbridge Co Inc, 144 Pearl St., 1918

New York Herald. Mar 22, 1912

New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #17326. (Nicolina Lener)

United States Census of 1910, New York State, New York County. W 12, ED 339. (2097 First Av.)

New York Tribune. Mar 15, 1910. p.1[↩] - New York Daily Tribune. Mar 21. 1912 p.2[↩]

- New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #17326. (Nicolina Lener)

1910 United States Federal Census. New York. Bronx. AD 32, ED 1469. (1739 Zegra Av.)

New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #14403. (Tomasso Lener)

NYT. Mar 21, 1912. p.1[↩] - The Sun. New York. Oct 30, 1911. p.2

The Sun. New York. Mar 21, 1912. p.3

NYT. Oct 30, 1911. p.20

Real estate record and builders’ guide. New York: F. W. Dodge Corp. v. 84 Jul-Dec 1909 Index. p.460

(The conveyance was likely made as a gift. It requested a mortgage around 70% lower than the properties estimated value: New York (City Record Office. Annual record of assessed valuation of real estate in the city of New York. New York. (1906-1911) [↩] - New York Herald. Feb 1, 1910. p.14

Entertainment license granted to Aristide Carbone: The City Record: Official Journal. New York: V.37. Oct 6, 1909. p.1

The City Record: Official Journal. New York: V.38. Jan 5, 1910. p.87

New York Herald. March 9, 1910. p.8[↩] - New York Herald. Mar 15, 1910. p.4

York Dramatic Mirror. Mar 26, 1910. p.8

New York Tribune. Mar 15, 1910. p.1[↩] - United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975. Westchester. Grantor index (Eastchester) 1898-1931.

The Daily Argus. Oct 5, 1910[↩] - Real estate record and builders’ guide. New York: F. W. Dodge Corp. V.88. Jul 8, 1911. p.22 & Jul 15, 1911. p.60

Real estate record and builders’ guide. New York: F. W. Dodge Corp. V.88. Jul 8, 1911. p.37

NYT. Jul 6, 1911. p.17 c7[↩] - The Evening World. Dec 16, 1912

The New York Press. Dec 16, 1912. New York Death Certificate. Manhattan #35154

New York Evening World. Dec 16, 1912

NYT. Dec 17, 1912[↩] - United States Census of 1910, New York State, New York County. W 12, ED 286. (2066 First Av.)

New York State Population Census, 1905; City: Manhattan; County: New York (400 E107th St.)

New York Evening World. Oct 30, 1911

The Sun. New York. May 24, 1909

NYT. Oct 30, 1911. p.20[↩] - New York Evening World. Oct 31, 1911

The Sun. New York. May 24, 1909

1910 United States Federal Census. Elmira, Chemung, New York. W 7, ED 28. (Inmate Frank Monaco) [↩] - NYT / New York Evening World / The New York Call / The Sun. New York / Oct 30, 1911[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- NYT / New York Evening World / The New York Call / The Sun. New York / Oct 30, 1911

New York Herald / New York Evening World / Oct 31, 1911

New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #17326. (Nicolina Lener) [↩] - New York Herald / New York Evening World / Oct 31, 1911

NYT. Mar 21, 1912[↩] - Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Jun 19, 1951[↩]

- The New York Press. Mar 21, 1912. p.1 & 3

New York Herald. Mar 22, 1912[↩] - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG 87, Daily Reports of United States Secret Service Agents, William Flynn Vol. 33. Dec 12, 1911.[↩]

- The New York Press. Mar 21, 1912. p.3

United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975. Westchester. Grantor index (Eastchester) 1898-1931[↩] - New York Herald. Mar 21, 1912

The New York Press. Mar 21, 1912. p.1[↩] - New York Herald. Mar 21, 22, 1912[↩]

- New York, New York, City Directory, 1911

New York Herald. Mar 24, 1912

The Sun. New York. Mar 23, 1912

New York Tribune. Feb 20, 1914. p.1[↩] - New York Tribune. Feb 20, 1914. p.1

NY Court of General Sessions. 1912. #91763 The People vs. Andrew Rege and Luigi Lazzazzara[↩] - NYT. Apr 23, 1911. p.9[↩]

- NYT. Apr 7, 1913. p.2[↩]

- The Evening Telegram. Oct 3, 1912. p.9

The New York Evening World. Oct 3, 1912. p.13

Waausau Daily Herald. Dec 23, 1912

The People of The State of New York vs Aniello Prisco. #89082 (Docket) 9 Aug 1912[↩] - Manuscript Files Related to “The Real Thing: The Expose and Inside Doings of Costa Nostra”, 1964 – 1964. John F. Kennedy Library[↩]

- New York Herald. Sep 3, 1912

New York Tribune. Sep 3, 1912. p.2[↩] - New York Call. Oct 4, 1912. p.3

Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Dec 16, 1912. p.4[↩] - The Evening Telegram. Oct 3, 1912. p.9

NYMA, DA Record of Cases #95249, The People vs. John Russomano (Memo in reference to the character of the defendant.) [↩] - New York Sun. Dec 17, 1912. p.16.

New York Tribune. Dec 17, 1912. p.16.

The Evening News. Dec 17, 1912.

Waausau Daily Herald. Dec 23, 1912

United States Census of 1910, New York State, New York County. W 12, ED 327. (Salvatore Mariano 2207 First Av.)

New York Herald. Dec 20, 1912. p.8[↩] - Court of General Sessions for New York County, The People of the State of New York against John Russomano. March 20, 1914

NYMA, DA Record of Cases #95249, The People vs. John Russomano (Memo in reference to the character of the defendant.)

The Fort Wayne Journal Gazette. Dec 12, 1915.

Antonio Capalongo’s real name was Antonio Vivolo – confirmed in private communication.[↩] - The Evening World. Feb 18, 1913. p.9

NYMA, DA Record of Cases #95249, The People vs. John Russomano (Memo in reference to the character of the defendant.) [↩] - New York Herald. Dec 6, 1913. p.7

New York Tribune. Oct 20, 1914

Court of Appeals. The People of the State of New York against Alessandrio Vollero, Case on Appeal. Vol 1. (1918) 226/587 PT1. p.473

The Evening World. Apr 11, 1913. p.10

The New York Herald. Apr 11, 1913. p.20[↩] - Ship: Tartar Prince. Mar 26, 1900. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957.[↩]

- Utica Herald Dispatch. Dec 19, 1911. p.1

Bridgeport Evening Farmer. Dec 23, 1911. p.1

The Sun. New York. Dec 19, 1911. p.1[↩] - The New York Herald. Apr 6 & 10 & 11, 1913

The Evening World. Apr 11, 1913. p.10

The Sun. New York. Apr 30, 1913. p.5

New York Evening World. Apr 29, 1913

Marriage Certificate (Manhattan) #21340 [↩] - The Sun. New York. Apr 19, 1913

The New York Herald. Apr 17, 1913

The Sun. New York. Apr 19, 1913

The New York Herald. Jul 21, 1916. p.1

NYT. Apr 27, 1913

Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette. Dec 12, 1915[↩] - New York Herald. Oct 5, 1913. Third Section. p.3[↩]

- The Times Democrat. Aug 2, 1913. p.3[↩]

- The Berkshire Evening Eagle. Oct 29, 1912. p.3

New York Tribune. Oct 24, 1912. p.2

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG 87, Daily Reports of United States Secret Service Agents, William Flynn. Vol.29 (Mar 8, 1910)

New York Tribune. May 23, 1915[↩] - The Times Democrat. Aug 2, 1913. p.3

The Evening World. Jul 26, 1913

New York Herald. May 18, 1915. p.7

New York, Sing Sing Prison Admission Registers, 1865-1939. #64408

Court of General Sessions for New York County, The People of the State of New York against John Russomanno. Mar 20, 1914[↩] - NYMA, DA Record of Cases #95249, The People vs. John Russomano (Memo in reference to the character of the defendant.) [↩]

- NYT / New York Tribune / New York Herald. Feb 20. 1914

Ship: Citta Di Milano. Dec 10, 1902. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. Angelo Lasco #A2122[↩] - The Brooklyn Daily Times. Nov 14, 1917. p.1

Court of Appeals. The People of the State of New York against Angelo Giordano, Record on Appeal. Court of General Sessions. 231/633 PT1. People’s exhibit #1 (Statement of Leopoldo Lauritano. Mar 27, 1918) [↩] - Court of Appeals. The People of the State of New York against Alessandrio Vollero, Case on Appeal. Vol 1. (1918) 226/587 PT1[↩]

- United States Census of 1910, New York State, New York County. W 12, ED 323. (306 East 116th)

Trow’s New York City directory, Aug 1910. p 1029 “Beer 2218 2d Av”

Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. p.111, 113

The New York Herald. Apr 10, 1913. p.1[↩] - The Daily Standard Union Brooklyn. Mar8, 1918. p.9

New York Marriage certificate: Manhattan #123324

The Standard Union Oct 12, 1916. p.3[↩] - NY Court of General Sessions. 1912. #91763 The People vs. Andrew Rege and Luigi Lazzazzara

Evening World. Nov 17, 1916. p.19[↩] - Court of Appeals. The People of the State of New York against Angelo Giordano, Record on Appeal. Court of General Sessions. 231/633 PT1. People’s exhibit #1 (Statement of Leopoldo Lauritano. Mar 27, 1918)

Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia. 111

The Barre Daily Times. May 18, 1915

Manuscript Files Related to “The Real Thing: The Expose and Inside Doings of Costa Nostra”, 1964 – 1964. John F. Kennedy Library

NYT. May 25, 1915. p.10 [↩] - New York Tribune. Apr 10, 1914. p.2

Polk’s (Trow’s) New York copartnership and corporation directory, boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx. New York. 1910. p.310[↩] - Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt.

R.L. Polk & Co.’s Trow general directory of New York City. New York City directory, 1916. p.211

The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi. Certificate of Incorporation. 1902 [↩] - New York Herald, Oct 8, 1915. p.1

New York Tribune. Oct 28, 1919. p.22[↩] - The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Dec 17, 1922. p.42

The Sun. New York. Aug 2, 1924. p.16[↩] - The New York Sun. Nov 11, 1939. p.14[↩]

- https://zola.planning.nyc.gov/l/lot/1/1678/1#15.8/40.790775/-73.935674[↩]