“Thousands of faces look from the swinging frames in the gallery of the Washington headquarters of the Secret Service. There are stories for these faces that stir the blood and compel one’s admiration for the genius that carries to temporary success some brilliant campaign of wrong-doing.” – John Wilkie, chief of the US Secret Service. (1905)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Italian law included a provision called domicilio coatto (forced domicile), a preventive policing measure that resettled suspected criminals on small islands near the mainland coast without the need of a trial or conviction. Another measure was sorveglianza speciale (special surveillance), an exceptionally strict surveillance period enforced on suspects and recently released prisoners.1

In 1908, New York Police Commissioner Bingham remarked,

“The lawbreaker’s life outside of prison in Italy is, in fact, passed in continual fear of the police and the carabinieri … it is not at all surprising that he should take advantage of the first opportunity to get to the United States, where he is unknown to the authorities and conditions are perfect for him to live upon the more helpless of his honest fellow countrymen.”2

An article from 1909, highlighted the favorable environment that criminals found in the US:

“Conditions in the United States could not have been better contrived for the Italian ex-convict driven from his native land by the rigorous punitive supervision of the police. Not only is he unknown to the authorities of law and order, but wherever he may go he finds himself among the southern Italians who are already familiar with the operation of the Mafia and the Camorra…”3

The attention of the press was drawn to the Mafia following the murder of Antonio Flaccomio in New York in 1888, the first officially recognized Mafia killing in the city.4 Front-page stories described the Mafia as “an organization which is so strange to this country as to deserve explanation from the press and surveillance by the police” and claimed it was an “acknowledged formidable enemy to the administration of justice in New York.”5

The national attention of America was again drawn to the Mafia after New Orleans Chief of Police David Hennessy was murdered while making his way home on October 15, 1890. The newspapers were flooded with stories about Hennessey being the first American victim of the Mafia. New Orleans, with its booming fish and fruit importing trade, had become a popular destination for Italian immigrants. The murder was thought to be connected to a long-waged battle between two factions of Italian stevedores, the Matrangas and the Provenzanos.6

Protesters, outraged at the jury’s failure to convict the suspects, marched on the New Orleans prison and killed eleven inmates, leading to a breakdown in diplomatic relations between Italy and the US. A report commissioned by the city’s mayor into the existence of secret societies in New Orleans stated that Hennessy had “a deeper knowledge of the Mafia and its methods than any other detective,” and that “Every man who had ever held a high position in police circles and every committing magistrate who has ever sat upon the bench in this city are convinced of its existence.”7

Two notable Mafiosi known to have fled Italy, who would later lead their own crime families in the US, were Ignazio Lupo and Giuseppe Morello. Lupo, born March 1877, fled Sicily after he killed a business rival in his Palermo store. Arriving in New York in 1898, he went into business with family members and later started his own wholesale grocery business.8 Morello, born in May 1867 at Corleone, traveled to America around the time he was accused of the killing of Anna di Prima in 1894 (she was a witness against him in a homicide case). He was charged with “belonging to a criminal association for robbery and homicide,” although there was insufficient evidence to prosecute him.9

Lupo and Morello both feature heavily in the history of American counterfeiting, which was dominated by Italian-born outlaws beginning in the late 1880s.10

The chief of the Secret Service stated in 1885,

“There exists a secret gang of Sicilian counterfeiters in this country with members in all the large cities … The gang are sworn to reveal nothing of their calling under an awful punishment.”11

Agent Andrew L. Drummond, head of the New York Division, responded,

“It has long been known to me that the Italian counterfeiters in the country from Palermo and all parts of Sicily are banded together and that to betray one of their members is death at the hands of some chosen member. This order is called the ‘Maffa.’”12

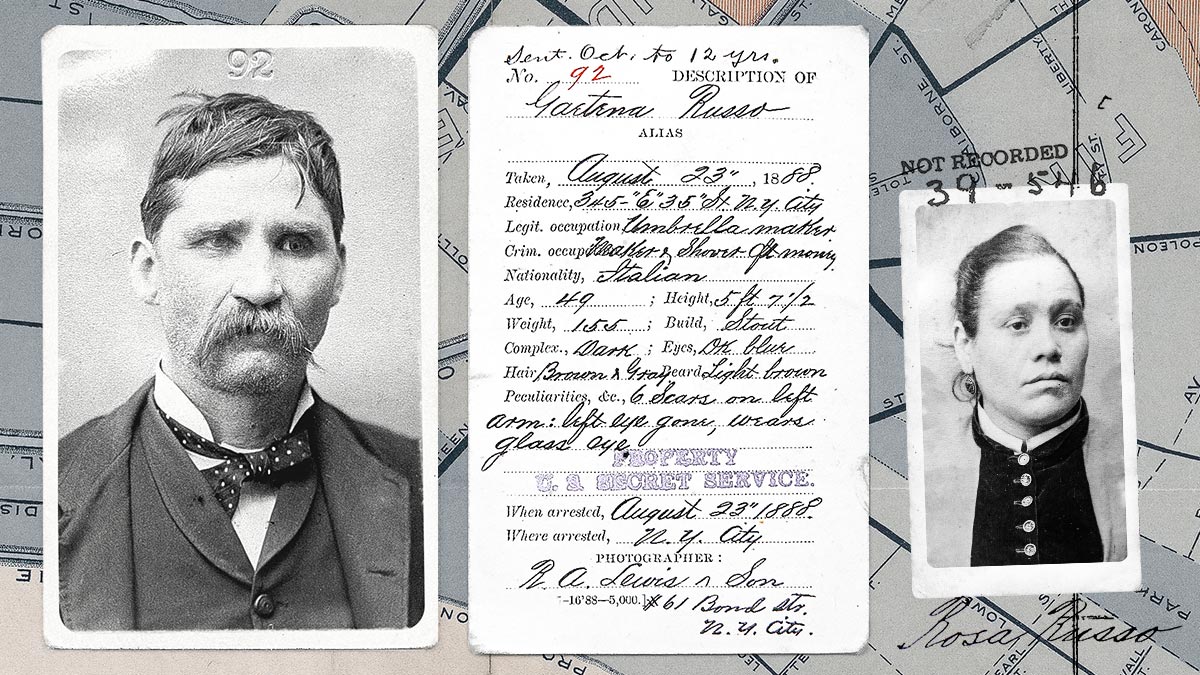

One notable counterfeiter mentioned in Drummond’s reply was Gaetano Russo, who arrived in New Orleans in 1862 and went on to have a chaotic and violent career. Russo was charged with murder of a fellow counterfeiter in Chicago but was acquitted after the “Italians swore him free.” He relocated to New York after the trial where he was acknowledged as “a leader among the Italians making counterfeit coins.”13

In 1885, rumors began to spread in New York that Russo was an informant. It became known that he’d previously received a life sentence in Louisiana for arson but was pardoned after serving just one year. Fearful counterfeiters began to shy away from their work and quickly saw their profits begin to fall. One of Agent Drummond’s spies reported that “the Society of Italians are pretty well broke in New York city” and that it had been proposed that Russo should leave the city or be killed.14

Russo traveled to Europe with his wife and worked with an engraver to produce $30,000 in new counterfeit US bills. He was captured following his return to New York in August 1888, with his gang being described as the first of any consequence since the 1878 capture of infamous counterfeiter William Brockway. As head of the outfit, Russo was sentenced to twelve years in Erie County Penitentiary. Also sentenced was Candelaro Bettini from Messina, an associate of those connected with the Mafia murder of Antonio Flaccomio.15

Bettini was released from Erie County Penitentiary in 1895. He married “Queen of the Counterfeiters” Salvatora Purpura, a wealthy tenement owner from Union Street, Brooklyn, who had strong ties to many of the criminal Palermitani (from Palermo, Sicily) in the area. Purpura also had international connections, including her associate Joe Raffone who was noted as having imported counterfeits worth $25,000 from Palermo into Boston. Acting as the importer for the gang, she arranged consignments of notes to be smuggled over from Italy and personally collected the shipments from the ship’s captain before bringing them back to Brooklyn.16

Bettini, who worked as the gang’s wholesale dealer, struck up a partnership with Nicola Taranto, a “cousin” from Messina, who sold the notes from his store on Roosevelt Street in Manhattan.17

Sixteen of the group were arrested in 1896 after distributing counterfeit notes known as the “Italian” $5 and $2 certificates across the north eastern US.18 Bettini criticized Taranto for making “a great mistake in selling the money to young fellows; he should have sold it only to the older men who had long experience in the business.”19 The hierarchy of the gang became apparent during a violent disturbance at Ludlow Street Jail. Nicola Taranto was observed ordering his men to yield using a countersign and passwords and was “seconded by Bettini his next in command.”20 Taranto was sentenced to five years, which his counsel described as a probable life sentence due to his chronic kidney disease. (Following his release in 1903, it was discovered that he had retired from counterfeiting altogether.)21

Letters found in Taranto’s store at the time of his arrest pointed “in a striking manner to Taranto as the head and chief of the Mafia as it exists in this country.” Some of the letters came from Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, where ten captured Mafia suspects confessed to working under orders received from New York and Philadelphia.22 Their leader, James Antonio Passarella, known as the “Bandit King,” had been sent from the “Mafia headquarters in Philadelphia” to oversee the gang and make regular reports back to Philadelphia and New York. When the gang needed dynamite for blowing up a house, a bomb was manufactured in Philadelphia and “sent by express.”23

Import businesses, restaurants, coffeehouses and barbershops provided useful distribution points and meeting places for counterfeiters. One notorious meeting place was a New York saloon at 8 Prince Street. The restaurant at the rear of the establishment was managed by Giuseppe Morello, possibly the first US Mafioso with the title of capo dei capi (boss of bosses).24 The saloon was often mentioned in Secret Service reports. One agent asserted “more counterfeiters have been arrested at this address than any other place I know, it is one of the worst joints in the city.”25

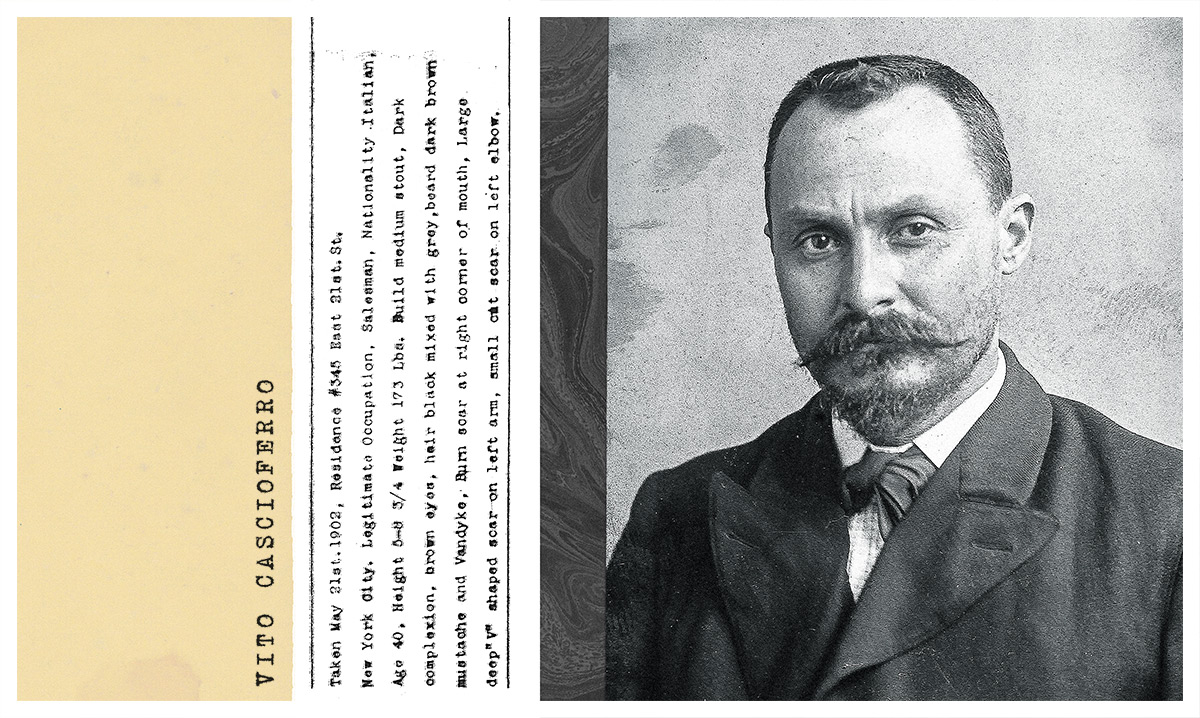

In 1902, Antonio D’Andrea, the future boss of the Chicago Mafia, was sentenced to thirteen months after passing counterfeit coins he had purchased from the owner of the Prince Street saloon. They were being manufactured by a gang led by a female counterfeiter, who was arrested along with the powerful Mafia leader Vito Cascioferro.26

Joseph Petrosino, who had been involved in the 1896 roundup of Passarella’s gang, was a renowned police officer credited by the commissioner of Immigration as having better qualifications than “any other man in the US for apprehending the lawless Sicilians.”27 In 1902, Petrosino received an anonymous letter about a counterfeit coin plant in New Jersey. The investigation led to the arrest of Vito Cascioferro, “probably the most powerful Sicilian cosca (clan) leader of the age.”28

Petrosino’s tip-off led to the capture of a gang thought to be responsible for 75 percent of counterfeit coins in the region. The arrests included Vito Cascioferro; Stella Frauto, an experienced female counterfeiter; Andrea Romano, the owner of the Prince Street saloon; and Salvatore Clemente, who became an invaluable informant to the Secret Service through the next thirty years.29

Cascioferro managed to escape conviction after some witnesses failed to identify him and others failed to appear at all.30 The following year, he was tracked around the city by Secret Service agents. They observed his meetings with many Italian counterfeiters, primarily Giuseppe Morello and members of his gang. In March 1903, he was seen trying to arrange passage back to Sicily before he disappeared from the city.31

- Griffiths, A. (19–). The history and romance of crime from the earliest time to the present day. London: The Grolier Society. 273

Garfinkel, P. (2018). A Wide, Invisible Net: Administrative Deportation in Italy, 1863–1871. European History Quarterly, 48(1), 5–33[↩] - Bingham, T. (1908). Foreign Criminals in New York. The North American Review, 188(634), 383-394[↩]

- White, Frank Marshall. (1909) How the United States Fosters the Black Hand. The Outlook. V93 New York: Outlook Co. 496[↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. “Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory” The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. 15[↩]

- Akron City Times (Nov 21, 1888) 1[↩]

- Nelli, H. S. (1976). The Business of Crime: Italians and Syndicate Crime in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. 24-27, 35-37

Wilkes Barre Times Leader. The Evening News. (Oct 20, 1890) 1

Pitkin, Thomas M. & Cordasco, Francesco. (1977). The Black Hand: A Chapter in Ethnic Crime. Totowa, N.J: Littlefield, Adams. 23–28[↩] - United States. Department of State. (1891). Correspondence in relation to the killing of prisoners in New Orleans on March 14, 1891. Washington: G.P.O.[↩]

- U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Guiseppe Calicchio et al, Transcript of Record. (1910) 462-467[↩]

- General Records of the Department of State, 1763–2002. Numerical Files, 1906 – 1910. M862 Roll 845. Giuseppe Morello criminal record.

Flynn, W. J. (1919). The Barrel Mystery. New York: The James A. McCann Company. 243-261

U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Guiseppe Calicchio et al, Transcript of Record. (1910) 456. [↩] - Johnson, D. R. (1995). Illegal Tender: Counterfeiting and the Secret Service in Nineteenth Century America. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. Table 1.8[↩]

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter referred to as NARA), RG 87, Daily Reports of Agents, (hereafter referred to as DRA). A.L. Drummond. Vol. 34 (Oct 16, 1885) [↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (Feb 9, 1890)

The Buffalo Commercial (Feb 18, 1890)

NARA. RG 29. Records of the Bureau of Prisons, 1870 – 2009, Inmate Case Files, 1902 – 1922, Gaetano Russo, Inmate No. 4840.[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. A.L. Drummond. Vol. 34 (3 Nov, 1885. 21 Jan, 16 Feb 1886)

Chicago Tribune (Jan 26, 1887) 5

New Orleans Republican (Mar 11, 1874) 5[↩] - The Buffalo Commercial (Feb 18, 1890)

Fort Scott Daily Tribune (Sep 4, 1888)

Buffalo Courier (Sep 18, 1888) 6

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Jun 26, 1896)

Fort Scott Daily Monitor (Nov 21, 1888) 3[↩] - Lebanon Daily News (Jun 4, 1896) 1

The Standard Union (Oct 22, 1892)

NARA, RG 87, DRA. G. Ray Bagg. Vol.8 (Oct 1895 – Jan 1896) [↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. G. Ray Bagg Vol. 8 (Jan 17, 1896)

The New York Times (Jan 18, 1896)

Harrisburg Telegraph (Jan 17, 1896) 1[↩] - The New York Times (Jan 18, 1896)

The Sun. New York (Jan 17, 1896) 3

United States Department of the Treasury. (1896) Annual report of the secretary of the Treasury on the state of the finances. Washington. 817-818[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. G. Ray Bagg. Vol.9 (Jun 13, 1896)

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.5 (Dec 12, 1901) [↩] - The New York Times (Mar 6, 1896) 10[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.5 (May 5,6, 1903) [↩]

- The Journal – “King of the Counterfeiters” (Jan 18, 1896)

The Philadelphia Times (April 24, 1896)

The Philadelphia Times (Feb 27, 1896) 5

Akron Daily Democrat (Jan 24, 1896) [↩] - The Philadelphia Inquirer (Apr 25, 1896)

Akron Daily Democrat (Jan 24, 1896)

Buffalo Courier (Jan 14, 1896) [↩] - Flynn, W. J. (1919). The Barrel Mystery. New York: The James A. McCann Company. 9

Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 46[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.6 (May 5, 1902) [↩]

- The Buffalo Times (Dec 7, 1902)

Chicago Tribune (Apr 16, 1903) [↩] - The Philadelphia Times (Feb 27, 1896) 5

The Daily Town Talk, Alexandria LA (Nov 8, 1905) 3[↩] - Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 40[↩]

- The Scranton Republican (Nov 28, 1902). 2

Buffalo Courier (Dec 7, 1902) 2

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn & New York Volumes (1902~1930)

Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. “Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory.” The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. 5[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 6 (May 29, Jun 4, 1902) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 6 (Mar 23, 1903) [↩]