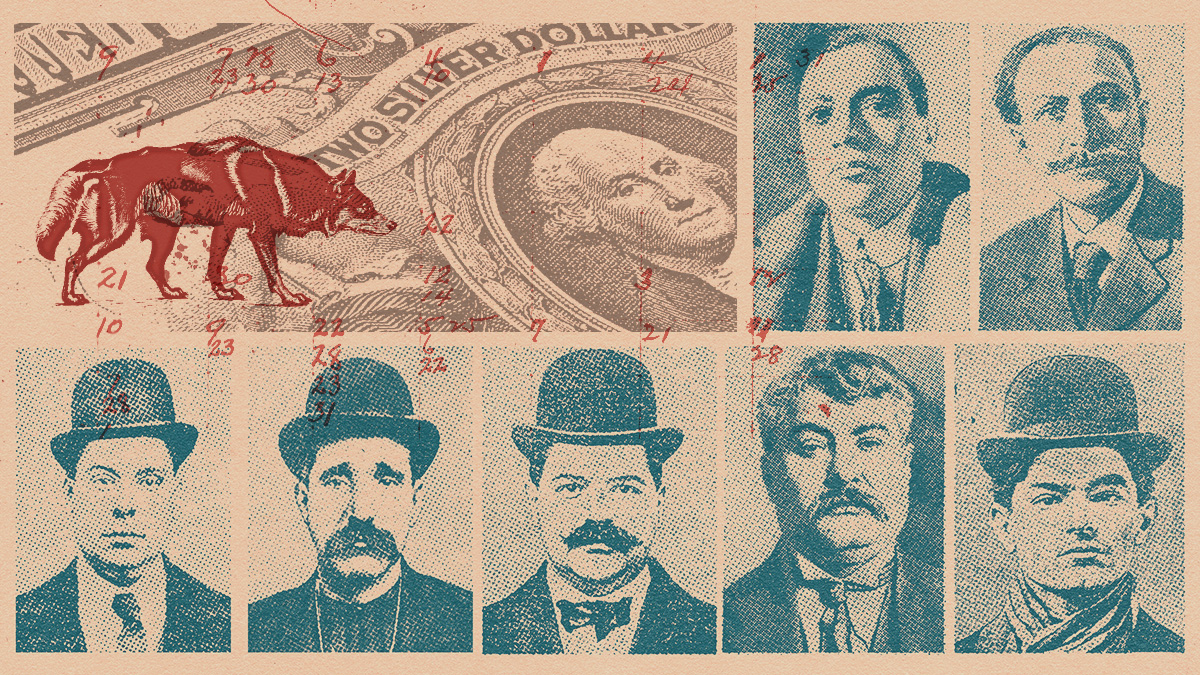

“The spirit of Giuseppe Morello, one time chief of the Black Hand, is broken. Lupo (the Wolf), the proud and haughty one, the carrier of the mandates of the dread society, has been seen to throw himself upon his face in despair and weep. The gang that gathered about them is dispersed, broken in fragments, and without a head. For not only have their chiefs been sent to federal prisons, but along with them eight most active lieutenants.” – Uncle Sam’s Modern Miracles (1914)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

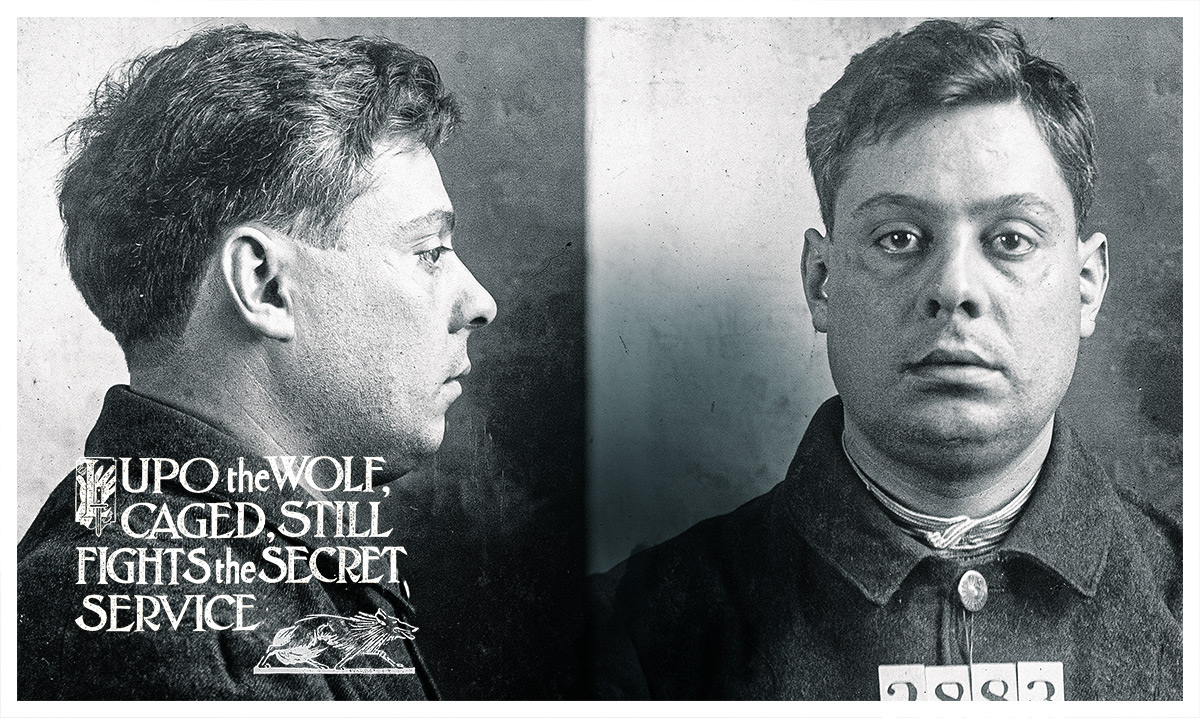

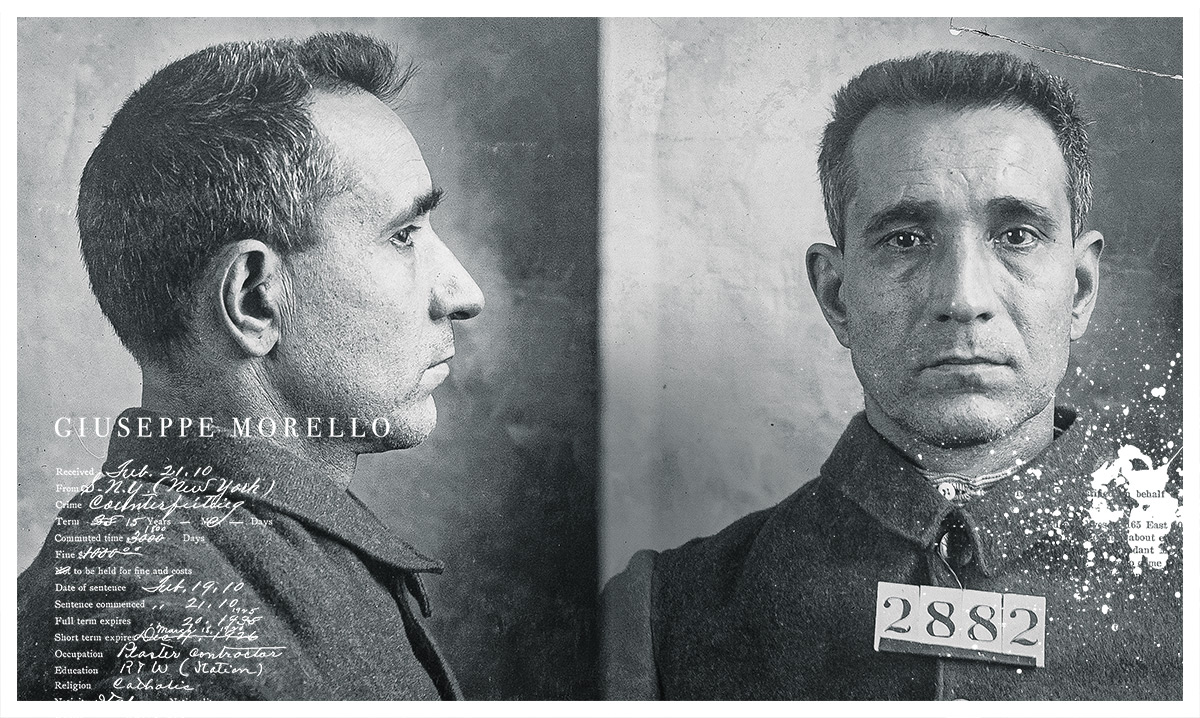

By late 1908, the Lupo-Morello combine was facing multiple problems. Before his death, Petrosino had hounded the two leaders to the point where they sent their legal counsel to threaten him with criminal libel.1 The pair’s business dealings were also facing investigations by the American Bankers Association.2 Lupo fled from New York in November, owing up to $100,000 to his creditors following a bankruptcy scheme.3 Just months later, the Italian government requested his extradition in connection with the 1898 murder of a Palermo business rival.4 He also had an outstanding indictment against him from a 1903 counterfeiting case.5

Morello faced problems from investors and lenders who threatened lawsuits and worse after the collapse of his construction/banking co-operative.6 His failed society, the Ignatz Florio Co-operative Association Among Corleonesi, was incorporated in 1902. The company built and sold many properties in New York at a time when shrewd speculators could construct New Law tenements with a $5,000 outlay.7

Described as a banking and real estate business, the corporation sold “memberships” or shares by subscription at $1 per month.8 The company’s secretary revealed that “whatever Morello said was always considered as law.” The secretary explained that members lost their investments through questionable financial dealings. A number of Bronx properties were used as security for Ignazio Lupo’s grocery purchases and were then lost when Lupo’s business failed, his inventory vanished and he fled his creditors.9

An associate later explained, “It was Morello who conceived the idea of counterfeiting the notes on a large scale. Sometime after the Co-operative Association failed, some of the members who had lost their money began to crowd Morello and threatened to kill him. Morello’s idea was to reimburse these men with counterfeit money.”10

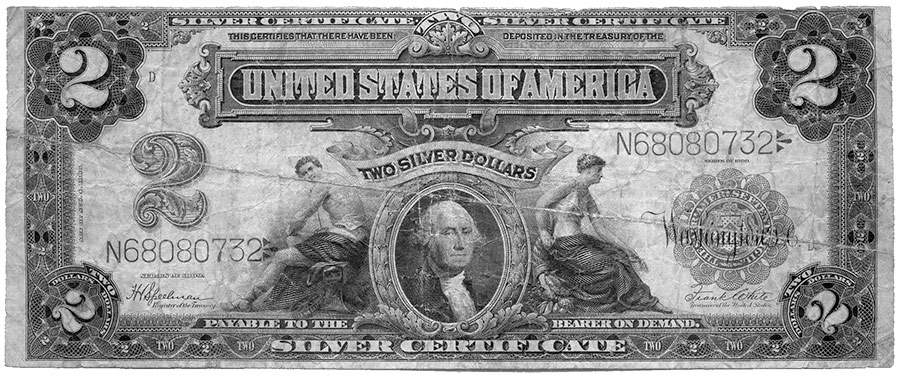

Morello’s business partner, Antonio Milone, ex-president of the failed Ignatz Florio Co-Operative, began the task of etching the lithographic plates for printing counterfeit Canadian five-dollar and US two-dollar bills.11 The band set up its printing operation inside farmhouses in Highland, New York, and over the next six months printed about $50,000 in counterfeits. Multiple problems with the quality of the notes needed to be addressed before buyers would accept them.12

In May 1909, the Secret Service began to receive complaints of counterfeit notes in New Orleans and across the Northeast.13 Agents were tipped off to suspicious activity at an East Ninety-seventh Street wholesale grocery belonging to Domenico Milone, one of the “Lupo crowd.” They promptly set up surveillance on the store and observed “secret conferences” held there.14

William Flynn of the Secret Service had tried to snare the gangs in 1903 by using an informant to purchase counterfeits with marked bills.15 His plan failed at the last minute when the Barrel Murder caused him to hand over investigations to the NYPD. Flynn resurrected the old ploy in 1909, and this time it worked. He used informant Sam Lucchino from Pittston, Pennsylvania, to purchase notes from the gang. 16Lucchino was an ex-Black Hander, who agreed to testify against the gang if he was given a position in the Secret Service. Flynn designated him a “temporary employee” to “give him some standing as a witness.” (He later became a private detective working with the Pittston police and federal authorities. Lucchino survived several assassination attempts before he was eventually killed in 1920.) 17

On November 15, shortly after Lucchino had purchased the counterfeits, Morello lieutenant Antonio Cecala, was arrested and found in possession of the Secret Service’s marked bills. Flynn contacted the Italian Squad to execute search warrants against the rest of the gang, which resulted in the arrest of Morello, his half-brother Nicola Terranova and eleven associates. Morello was captured at his home, 207 East 107th Street, where the police uncovered “some very damaging ‘Black Hand’ letters, which he had evidently sent to different Italians and upon receiving them, they paid the demand of Morello …” Additional arrests were made in the following months. Lupo was eventually captured in Brooklyn. The assistant district attorney stated, “It is the biggest round-up of counterfeiters in the history of the country.” 18

A letter discovered in Morello’s apartment was addressed to Rosario Dispenza, described as “one of the men highest up in the Chicago Mafia” and a business partner of Antonio D’Andrea. The letter revealed the existence of a secretive Mafia Council and Assembly: “Dear Friend … Regarding the Council, you have no right to be present in the meetings. The Council is divided and separated from the Assembly… Have I explained myself? This is for your guidance …”19 Further details of the system were later revealed in the memoirs of Mafioso Nicola Gentile. He described one particular meeting of the General Assembly as a “gathering all of the representatives in the United States,” which was then followed by the General Council – a closed-door vote of the crime family heads.20 The system, which stood as “New World examples of the older Sicilian regional and provincial commissions” was replaced in 1931.21

Lupo, Morello and six of their associates were put on trial in January 1910. The government’s chief witness was Antonio Comito, an outsider who had been compelled to print the counterfeit notes for them. After his arrest in early January, he promptly gave the Secret Service his full account of how the gang had produced the counterfeits, recalling details of meetings and conversations he had overheard.22 Comito revealed the gang had been waiting for news from Palermo, and when they learned of Petrosino’s murder “they were all elated, and consumed wine, and had a feast.”23

During trial, a US Marshall discovered a knife stuck into his office wall. The court was then transformed into an “armed camp” as the government feared attempts to liberate the prisoners or influence witnesses. The judge received several Black Hand letters threatening his life, and gun cartridges were left scattered under court seats apparently to intimidate witnesses and spectators. Comito was the first witness called by the government, he gave a lengthy testimony against the gang under the guard of armed marshals and Secret Service agents.24

The trial concluded on February 19, 1910, with all eight defendants convicted and sentenced to hard labor at Atlanta Penitentiary. Ignazio Lupo was sentenced to thirty years; Giuseppe Morello to twenty-five years; Giuseppe Palermo, who acted as financier, to eighteen years; Antonio Cecala, who distributed the notes, to fifteen years; Giuseppe Calicchio, a printer who helped with production, to seventeen years; Vincenzo Giglio and Salvatore Cina, owners of the property where the notes were printed, to fifteen years; Nicholas Sylvester, a young criminal associate, to fifteen years.25

When Flynn was asked about the group’s political influence, he replied, “The strongest I know of. It is almost impossible to combat it. It comes from both political parties.”26 The gang was depending on the political influence of a Republican district leader in New York to assist with an appeal, they also negotiated with a Chicago politician who claimed he could free Morello for $15,000.27 Just over a year later, enough money was raised to send the case to the Circuit Court of Appeals, but the original judgment was affirmed.28

Lupo’s brother, Giovanni, was reported to have spent $65,000 on lawyer’s fees and endeavored to have the Supreme Court review the case. He also gave interviews to the press accompanied by a disgruntled former Secret Service agent. The agent criticized Chief Flynn and accused the Secret Service of using a counterfeiter as a “decoy” and employing ex-convicts. However, a grand jury later dismissed the agent’s claims and Flynn sued him for defamation.29

Ten months after the trial, the bulk of the counterfeit notes had not been discovered and were still in circulation across the city.30 Some of the notes had been stashed in a feed store on East 108th Street belonging to employee of Giuseppe Morello’s Ignatz Florio Society.31 The remaining notes were later sold to a counterfeiter with connections to Mafioso Manfredi Mineo.32

Thirteen more arrests were made in December. Giuseppe Boscarino, the gang’s distributor was sentenced to fifteen years, with Comito and Lucchino appearing again as government witnesses.33 Detectives recalled Boscarino’s connections going back to 1903, when he was involved with the distribution of the “Morristown Five” counterfeits at the time of the Barrel Murder. Following the additional arrests and Boscarino’s conviction, government officials believed they had “demonstrated that counterfeiting is a dangerous business that is unpopular with the authorities and dangerous to pursue.”34

Andrew Drummond, the ex-chief of the Secret Service who had battled Italian counterfeiters in 1885, congratulated Chief Flynn on his achievements and for ridding the community of “eight men more dangerous to life, I believe, than any eight men I ever saw tried for counterfeiting.” The US attorney for the Southern District of New York told Flynn, “I consider the conviction and sentences in this case, one of the greatest victories that this office has attained in many years.”35

- Washington Post (Jul 12, 1914) 6[↩]

- U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Guiseppe Calicchio et al., Transcript of Record. (1910) 420[↩]

- Black, Jon (2014) The Grocery Conspiracy. https://www.gangrule.com/events/the-grocery-conspiracy[↩]

- NARA. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. 1906-1910. Numerical File: 16606-16649/25. Roll 968. p 928.[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.28 (Nov 23, 1909) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.28 (Nov 22, 1909) [↩]

- The New York Times (Sep 13, 1903) 30[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 9 (Apr 29, 1903) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol. 33 (Dec 4, 1911)

Black, Jon (2014) The Grocery Conspiracy. https://www.gangrule.com/events/the-grocery-conspiracy[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn (Feb 10, 1913) Statement of Salvatore Cina[↩]

- Certificate of Incorporation of the Ignatz Florio Co-operative Association Among Corleonesi. 1902

Flynn, WIlliam. J. (1919) The Barrel Mystery. James A. McCann Company. 93[↩] - U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Guiseppe Calicchio et al., Transcript of Record. (1910)

Confession of Antonio Comito. Lawrence Richey Papers. Black Hand Confessions, 1910. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library.[↩] - Flynn. The Barrel Mystery. 31[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.27 (Oct 1909)

Flynn. The Barrel Mystery. 39[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.9 (Apr 9, 14, 1903) [↩]

- Flynn. The Barrel Mystery. 37[↩]

- The Wilkes Barre News (Feb 25, 1907) 2

The Baltimore Sun (Apr 27, 1907) 10

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.28 (Nov 27, Dec 30, 1909)

The Wilkes Barre Record (Jul 9, 1915) 18

The Plain Speaker (Apr 21, 1922) 3

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.28 (Jan 15, 1910) [↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.28 (Nov 15, 1909)

The Washington Post (Jan 11, 1910) 9[↩] - Belvidere Daily Republican (Jan 23, 1914) 1

Chicago Tribune (Jan 24, 1914) 1

Flynn. The Barrel Mystery. 207[↩] - Translation of Nicola Gentile article by Felice Chilanti in Paese Sera. Rome (Sep 14, 1963) [↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. 13

Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 131[↩] - Buffalo Evening News (Jan 27, 1910)

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 28 (Jan 4, 12, 1910) [↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.28 (Jan 7, 1910) [↩]

- The Buffalo Enquirer (Jan 28, 1910)

The Washington Post (Jan 27, 1910)

Vancouver Daily World (Jun 6, 1914) [↩] - U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Guiseppe Calicchio et al., Transcript of Record. (1910) [↩]

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Jun 3, 1912) [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.29 (May 13, 1910)

NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol.35 (Apr 3, 1912) [↩] - Circuit Court of Appeals, Second Circuit. #263 Calicchio et al. June 19, 1911[↩]

- The Burlington Free Press (May 23, 1912) 3

The Syracuse Herald (May 31, 1912) 21

The Washington Times (Jun 6, 1912) 11

The New York Times (Jun 3, 1912) [↩] - New York Tribune (Dec 2, 1910) 2[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.28 (Nov 18, 22, 1909)

The Trow copartnership and corporation directory of New York City (1912) 172 [↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.29 (Jun 2, 1910)

Counterfeiter Carmelo Cordaro connected to Mineo: NARA, RG 87, DRA. New York. Vol.32 (Jul) [↩] - New York Tribune (Dec 2, 1910) 2

Pittston Gazette (Dec 6, 1910) 1[↩] - The New York Times (Dec 11, 1910) 6 [↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol.29 (Feb 22, 1910) [↩]