“Petrosino was a great man, a good man. I knew him for years, and he did not know the name of fear. He was a man worth while. I regret most sincerely the death of such a man as Joe Petrosino.” – Theodore Roosevelt (1909)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

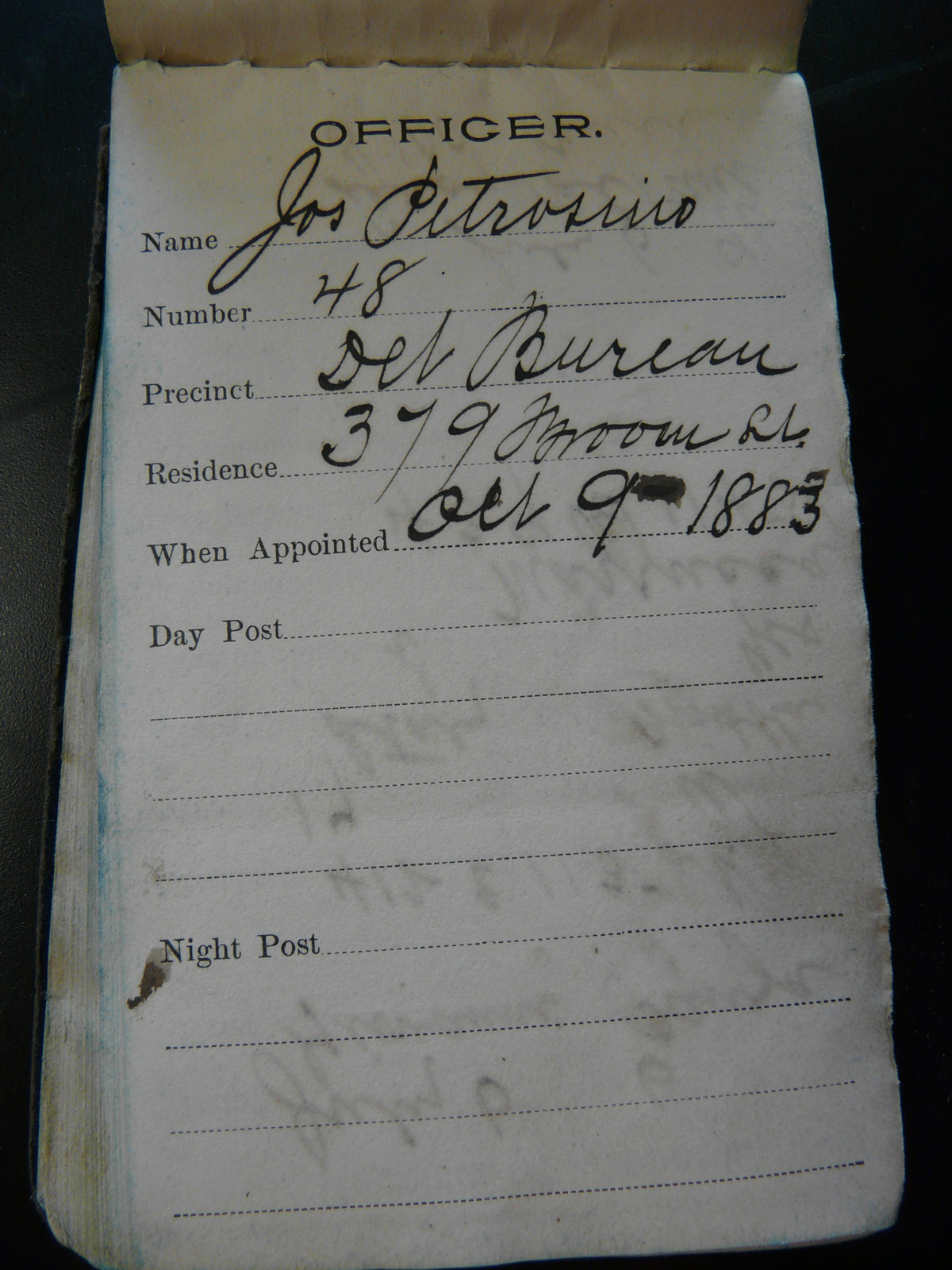

Joseph Petrosino, born 1860, in Padula, southern Italy, traveled to America as a boy. He joined the ranks of the NYPD on October 9, 1883, having already worked as an informer for the department.1 Petrosino was known for his hard-hitting methods, “what he accomplished was by sheer hard work and certain bulldog tenacity, combined with a complete knowledge of the of the habits and manners of the Italian criminal.”2

Petrosino was involved with countless Black Hand cases, and with most high-profile Mafia cases of the era, including the capture of Vito Cascioferro in 1902 and the Barrel Murder in 1903. He also apprehended the notorious Camorra leader Enrico Alfano, who occupied “a not dissimilar place in Naples to Vito Cascioferro in the Sicilian Mafia.”3 Alfano was extradited to Italy, where he was later sentenced to thirty years’ imprisonment following the much-publicized Camorra trials in Viterbo.4

Under the watch of Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, Petrosino was promoted to detective and quickly reached detective sergeant by the time Roosevelt left for Washington. In September 1904, he was placed in command his own “Italian Squad” of five plain-clothes detectives to suppress crime in the Italian districts.5

In the first year of its existence, the squad made 700 arrests.6 Facing a surge in Black Hand crimes, Petrosino requested to increase the squad from five to thirty detectives, and gave the following dramatic statement: “Unless the Federal Government comes to our aid, New York will awaken some morning to one of the greatest catastrophes in its history. You may think I am foolish making this statement, but these ‘Black Hand’ blackmailers are growing bolder every day. In a little while they will turn their attention to the American people and pursue the same tactics and methods they now employ in dealing with the Italians. Not even in Italy does such a condition exist as in New York at the present day.”7

In January 1906, Theodore Bingham, a retired Army brigadier general from West Point Military Academy, was appointed NY Police Commissioner and expanded the Italian Squad’s manpower.8 He also recommended the formation of a secret branch of the Detective Bureau recruited from civilians, noting “every member of the Police Force in New York City is known to or quickly becomes known to the criminals of every class.”9

The 1907 Immigration Act made it possible to deport foreign criminals within three years of their arrival in the US, but its execution was problematic. Any jail time that criminals spent in the US counted toward their three-year residence. A census of 990 alien convicts showed 319 who had been convicted within the last three years, 58 percent of which were Black Handers ineligible for deportation by the time of their release.10

Commissioner Bingham started a plan in December 1908, to send Petrosino to southern Italy to gather evidence against Italian criminals in America. Deputy Commissioner Arthur Woods wrote to the Department of State, “We do not want to make this a formal visit. We want to send Lt. Petrosino over rather on the quiet in order to get information which takes forever if we ask for it officially, and which we find great difficulty in getting at all when we try through private agents.”11

Petrosino left New York and sailed for Italy on February 9, 1909,12 but by the time he docked in Genoa on February 21, his whereabouts and mission were already revealed in the American press. Commissioner Bingham, who had battled with city aldermen to fund a secret branch of the Detective Bureau since 1906, had finally secured funding via private donations. He announced Petrosino as leader of the secret force but told the press that he had not seen him, “Why, he may be on the ocean, bound for Europe for all I know.” 13

Petrosino’s presence in Italy had made the Italian papers by the time he arrived in Palermo on February 28. After checking into Hotel de France on the Piazza Marina, he visited the American consul, William Bishop, and then set to work gathering evidence from the courthouse. On the evening of March 12, 1909, Petrosino was shot and killed while walking through the Piazza Marina.14

The Palermo Police Commissioner Baldassare Ceola began his investigation of the killing with three groups of potential suspects:

- Sicilian Mafiosi who sought to preserve their access to the US;

- Black Hand criminals in America who feared deportation; and

- already deported underworld figures, like Paolo Palazzotto, who wanted revenge

Ceola wrote “Petrosino’s arrival in Palermo, frightened too many people and threatened too many interests. For this reason, a regular international coalition was organized against him.”15

Ceola, the NYPD and the Secret Service received thousands of tips from people claiming to know the identity of Petrosino’s killer. One letter sent from Brooklyn named Carlo Costantino and Antonio Passananti as the killers working under the orders of Paolo Orlando, chief of the Castellammaresi Mafia in Brooklyn.16 Costantino and Passananti were reported to have visited Vito Cascioferro and were seen in Piazza Marina on the day of killing.17 Just three months before Petrosino’s killing, both Costantino and Passananti had been part of a large bankruptcy conspiracy in New York involving Ignazio Lupo and other grocers, and were noted to have left the city shortly after the press broke the story of Petrosino heading for Italy.18

Ceola concluded that Cascioferro was the “brains” of the conspiracy assisted by Costantino and Passananti, with Giuseppe Morello being the instigator. He also named thirteen collaborators, who had aided with the set-up of the killing and the escape of the assassins. However, all suspects in the case were eventually released due to lack of evidence.19

Ceola’s report mentioned Ignazio Lupo as a suspect, since deportation proceedings had been started against him just months before Petrosino’s killing.20 In 1910, a Secret Service informant recalled a comment from Ignazio Lupo’s brother Giovanni: “How did you like the Petrosino affair, no one knows now, and no one will know.” Giovanni described two killers as connected to the grocery business, one established by Ignazio Lupo, “neither of them are known to the police and were never suspected.”21

A month later, the same informant attended a meeting held in the store of Giovanni Lupo, who was likely the interim boss of the gang following his brother’s imprisonment.22 After the meeting, the informant walked to the ferry accompanied by a gang member who discussed the Petrosino murder with him: “Petrosino was killed because he had slapped Lupo and heaped personal abuse on him … not because he was detective and had to do his duty, but because he had no right to strike Lupo.”23 That explanation was backed up by witness accounts printed in the New York Times, alleging Petrosino had gone to Lupo’s Mott Street store in late 1908 and struck him, knocking Lupo to the floor.24

Antonio Vachris of the Italian Squad took up the dangerous mission of completing Petrosino’s work. He traveled to Sicily and returned with the names of over 500 Italian ex-convicts.25 In May 1911, Police Commissioner Waldo disbanded the Brooklyn Italian Squad and reduced the Manhattan branch to just four men. Vachris told a Kings County grand jury that the closure would practically undo all the squad’s work done in Sicily. Soon after that testimony, he was transfered to precinct duty in the Bronx – a three-hour journey from his home. His request to retire from the force was denied for a year until the Supreme Court ordered Commissioner Waldo to allow him to leave. 26

Vachris was questioned by the press at the time of his retirement. “Is it not true that Italian crimes have diminished in a great measure of late in New York City?” Vachris was asked. “Diminished? Why, it is worse than ever. The kidnapping of children is going on weekly. Nothing is said about it. Within the last six months there have been three or four cases. No arrests are made. It is the same with bomb throwings. They are being done on the East Side at the rate of two a week. Nobody pays any attention to them now.”

“How about murders among Italians?” the veteran detective was asked. “More than ever. Murders among Italians are of weekly occurrence and the records will show that I am right. There are about twenty-five Italian detectives sprinkled through the city, but they are not working as a unit any longer and they cannot accomplish much. They are for the most part faithful men, but the system of service has been so changed that their work is futile.”27

At the time of Petrosino’s death the Italian Squad had made an impressive 3,557 arrests with a 36 percent conviction rate.28

The tireless work of Joseph Petrosino, who lost his life pursuing the likes of Lupo and Morello, is remembered today in the US by a park in Manhattan near the location where Petrosino made his home. The NYPD Columbia Association presents an annual award in his name. In Italy, the Petrosino home in Padula is now a museum dedicated to telling his life story, and a plaque honouring Petrosino stands in Piazza Marina close the spot where he was killed in 1909.

- Petacco, Arrigo (1974) Joe Petrosino. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. 34-38

Policeman’s Record and History of Arrests. Joseph Petrosino. 1896

The Standard Union. Brooklyn (Sep 13, 1904) 9[↩] - White, Frank Marshall (1909). A Man who was Unafraid. Harper’s Weekly. Vol.53 Part 1. New York: Harper’s Magazine Co. 350[↩]

- Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 106[↩]

- New York Tribune (Jul 9, 1912) 1[↩]

- Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 39

McAdoo, William (1906) Guarding a Great City. New York: Harper & Bros. 154[↩] - White, Frank Marshall (1907). New York’s Secret Police. Harper’s Weekly. Vol.51 Part 1. New York: Harper’s Magazine Co. 350[↩]

- The Bemidji Daily Pioneer (Oct 19, 1905) 1

The Boston Globe (Oct 19, 1905) 7[↩] - Brooklyn Times Union (Dec 20, 1906) 2

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Dec 9, 1910) [↩] - New York Police Department. Annual Report 1906. 22 & 1907. 24[↩]

- White, Frank Marshall (1909). How the United States Fosters the Black Hand. The Outlook v.93. 495[↩]

- NARA. RG59. General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. Numerical Files, 8/1906 – 1910. Numerical File 13495-13497. M862. Roll 845.

White, Frank Marshall (1909). The Black Hand in Control in Italian New York. The Outlook v.104. 861[↩] - Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 118[↩]

- New York Police Department. Annual Report 1906. 22 & 1907. 24

The Sun (Feb 7, 1908) 2

The New York Times (Feb 20, 1909) 2

Norwich Bulletin (Feb 20, 1909) 1

The Sun (Feb 20, 1909) 3[↩] - Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 146-149[↩]

- Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 165[↩]

- Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 169

Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. 52[↩] - Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 151-152[↩]

- Black, Jon (2014). The Grocery Conspiracy. https://www.gangrule.com/events/the-grocery-conspiracy

New York Evening Telegram (Apr 6, 1909) 1[↩] - Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 170-174, 181[↩]

- Arrigo. Joe Petrosino. 172

NARA. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. 1906-1910. Numerical File: 16606-16649/25. Roll 968. p 928.[↩] - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter referred to as NARA), RG 87, Daily Reports of Agents, (hereafter referred to as DRA). William J. Flynn. Vol. 29 (Mar 22, 1910) [↩]

- Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory. 38[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn. Vol. 29 (Apr 15, 1910) [↩]

- The New York Times (Mar 17, 1909)

Asheville Citizen Times (Nov 20, 1909)

Press and Sun Bulletin (Nov 18, 1909) [↩] - NARA. RG59. General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. 1906 – 1910. Numerical File 13495-13497. M862. Roll 845[↩]

- The Brooklyn Citizen (Jun 22, 1911)

Brooklyn Times Union (Jun 30, 1911)

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Sep 30, 1912) [↩] - The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Oct 22, 1912) 2[↩]

- White, Frank Marshall. (1910) Against the Black Hand. Collier’s. Vol.45. 19[↩]