Incorporated in 1902 by Mafia boss Giuseppe Morello, the company traded New York real estate and constructed tenements in the city. The company ran into serious financial problems during the 1907 Bankers’ Panic and anxious associates threatened to kill Morello while the business faced multiple lawsuits.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In 1902, New York City’s working-class were facing soaring rental costs and a shortage of available accommodation. New building laws had come into effect causing a slow-down in the construction of new tenements. The demand for apartments, along with the opening of the city’s new subway in 1904, led to dramatic growth in construction across the city.1

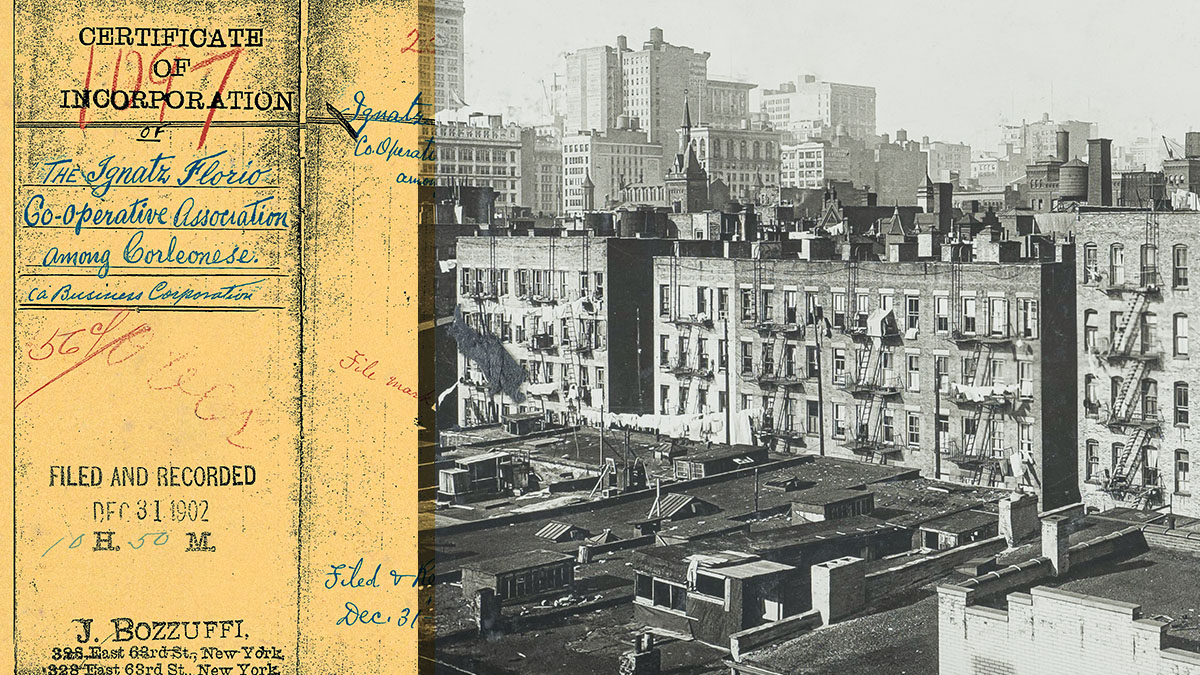

In December 1902, Mafia boss Giuseppe Morello entered the real estate business. He incorporated “The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi”. It described itself as being formed for “the promotion and engagement of mutuality and reciprocity in industries and commerce through the establishment of Cooperative stores and factories… “. The Co-op’s starting capital stock was 50 shares with a par value of $24 each.2

The Co-op’s directors were:

❖ Giuseppe Morello. 329 E 106thStreet

The US mafia boss was president of the Co-op.

❖ Antonio Biagio Milone. 335 E 106th Street

Milone was Giuseppe Morello’s third cousin3 and worked as both treasurer and secretary. In 1911, he lived with his brother Otto in the Bronx. His neighbors, who were nervous of his criminal reputation, couldn’t explain the source of his apparent wealth.4

❖ Francesco Badolato. 2085 2nd Avenue

Badalato arrived in New York in 1890, aged 22. In 1894 he married Maria Lo Monte, the sister of Fortunato Lo Monte. After the deaths of the Lo Monte brothers in 1915, he took ownership of their E 108th Street grain store located in the infamous ‘Murder Stables’.5

❖ Sebastiano Di Palermo. 337 E 106th Street

Di Palermo first arrived in New York in 1886, and later managed a saloon in the basement of 337 E 106th Street adjacent to the Co-op’s office.6 He leased the saloon from the tenement owner, Paolo Orlando who ran a contracting business with Angelo Gagliano called the “Trinacria Co-Operative”. In 1907, Gagliano was locked-up for sending an extortion letter after losing money on a plastering contract. In 1911, the Secret Service received a tipoff that both Orlando and Gagliano were gang bosses.7

❖ Marco Macaluso. 230 E 107th Street

Macaluso arrived in New York in 1887 aged 12. His brother-in-law Rosario Parisi was a first cousin to Antonio Milone and third cousin to Giuseppe Morello. He was the father of 1960’s Lucchese Family consigliere Mariano Macaluso.8

❖ Giovanni Di Miceli. 638 E 138thStreet

By 1906, the Co-op had added two new directors – Giovanni Di Miceli and Nene Guidera, with Di Miceli’s brother-in-law, Salvatore Castro, joining as the Co-op’s secretary (Di Palermo, Badalato and Macaluso were no longer listed as part of the company).9 Di Miceli arrived in New York around 1903. His residence in 1907 was listed as 638 E 138th Street which was constructed by the co-op. A cousin, Morris Di Miceli, worked as a contractor and superintendent for several of the Co-op’s construction projects.10

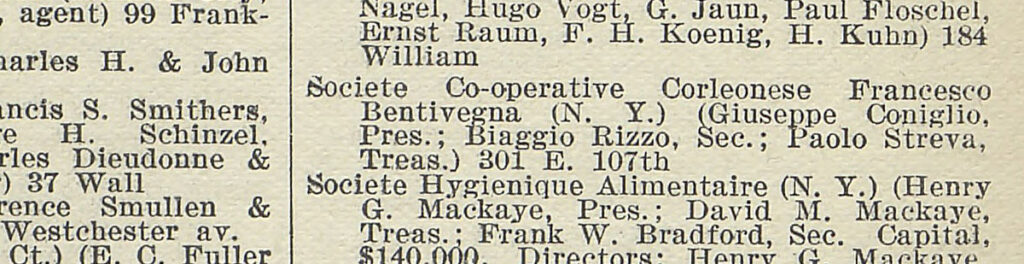

Another company named the “Francis Bentivegna Corleonese Company” was incorporated in late 1905. It included two Florio Co-op directors, Milone and Guidera, and by 1908 it included four Florio men.11

The Bentivegna Company name was similar to a previous Harlem co-operative called “Societa Co-operativa Corleonese Francesco Bentivegna”. It was incorporated in 1891 and based on E 107th Street. It ran until 1905 when it faced legal issues with a real estate deal. In 1895, the company president was Giuseppe Coniglio with Biaggio Rizzo as secretary and Paolo Streva as treasurer.12

The Florio Co-op was originally based at 335 E 106th Street where it also operated an “immigrant bank” offering credit and other services to its customers. There were more than 500 immigrant banks in New York City, many of which were unauthorized and irresponsibly managed. Their customers were distrustful of American institutions and often ignorant of banking methods. Many of the banks invested in real estate as either lenders or builders.13

The small banks would often commingle customer’s savings deposits with investments associated with other business ventures.14 A 1910 report on immigrant banks by the Immigration Commission stated:15

The affairs of the bank and of the proprietor are, as a rule, indistinguishable … the proprietor is at liberty to use the funds of the bank for his own purposes … The temptation to speculate with or to use for living expenses the funds in–trusted to them has also proven the downfall of many of these bankers. In general, the proprietor’s investments are the only security afforded the patrons of his bank.

Membership to the Florio Co-op was charged at $1 per month. Passbooks stamped with “Ufficio Bancario Societe Cooperative Corleonese Ignatz Florio” were issued to members to record financial transactions. It was estimated that the Co-op had around 150 shareholders, who were described as “poor and hard-working people who have invested their earnings”. The Co-op’s profits were shared with the stockholders as either stock or cash dividends.16

In 1906, a special meeting of shareholders voted favorably to increase the Co-op’s capital stock from 12 to 2000 shares at a par value of £100 each.17

Tenement construction required access to short-term mortgages and drew developers into an elaborate network of credit providers, contractors, and legal firms. Builders were left vulnerable to economic downturns due to the loan structures that were offered. They first had to borrow the capital to purchase properties at inflated prices, and would then need to secure further mortgages to finance the different stages of construction, all while paying interest on the loans. Developers required a fast turnaround on their projects to make a profit.18

The Co-op purchased or built the following tenements in New York City:

❖ East 105th Street

In 1904, the Co-op purchased two 6-story tenements at 319–325 E 105th Street. They had been built by Stefano La Sala at an estimated cost of $70,000. La Sala’s business address was 335 E 106th street, the same as the Co-op’s office.19

❖ East 101st Street

In 1904, Co-op treasurer, Antonio Milone, took out a mortgage on a 6-storey tenement at 332 E 101st Street for $18,650. He then transferred ownership to the Co-op with a mortgage of $22,500.20

❖ East 109th Street

In 1905, the Co-op applied to construct three 6-storey tenements at 311–315 E 109th Street at an estimated cost of $45,000. In January 1906, just weeks after the buildings were completed, Giosue Gallucci purchased a facing property at 318 E 109th Street which became his home and place of business. The Co-op sold the completed buildings to the recently incorporated “Francis Bentivegna Corleonese Company”.21

❖ East 80th Street

In 1906, a loan for $55,000 was taken to construct two 6-storey tenements with 28 apartments at 512–516 E 80th Street.22

❖ The Bronx

Properties on E 140th Street were purchased during 1905. The Co-op also took a $89,000 loan to build five 4-story tenements on Tinton Avenue.23

Also in 1905, the Co-op purchased property on the south side of E 138th Street. The plan, at an estimated cost of $140,000, was to erect four 6-story tenements with hot running water and steam heating. Construction began in March 1906 and was completed a year later at a total cost of $160,000. Half-way through the project the Co-op’s shareholders voted to increase its capital stock from 12 to 2,000 shares. 24

A month after the project was completed, the Co-op took a $100,000 loan to expand the project by building four abutting tenements on the north side of E 137th Street.25

In September 1907, the Co-op began to reorganize its portfolio. Two tenements on E 138th Street were conveyed to Ignazio Lupo. Both the neighboring tenements were conveyed to another Palermitani Mafioso, Pietro Inzerillo.26

A new $50,000 mortgage at 6% interest was taken on the E 137th Street tenements. The money lenders were a group that included: Salvatore Manzella, a grocer with business ties to Lupo; Biagio Calandra, a wholesale fruit dealer who had been tried for murder in 1906 and also had business connections with Lupo; Frank Fallotico; and John Rumore, a Morello Family associate and director of the “J. Rumore Realty Company”.27

The group were also assigned the Co-op’s mortgages held on the Tinton Avenue properties. The Co-op’s other properties further south on E 80th Street were conveyed to John Rumore and Frank Fallotico.28

Other money lenders for the E 137th Street property included Carmelo Naso, a director of the “The Co-Operative Society of Sicily” based on Prince Street.29

The reorganization of the Co-op’s portfolio painted a confusing picture. Several of its tenements had been conveyed to Mafioso, some had been transferred to nervous lending firms to hold as collateral security, and others were financed by close associates. The company was likely over-leveraged at this stage.30

During 1905–1906, New York had experienced a construction boom with large sums of capital borrowed at inflated interest rates. New York’s population was expanding by approximately 130,000 people per year but builders were providing accommodations for twice that figure. The number of tenements constructed broke all previous records with twice the amount of money invested in them than the entire city of Chicago spent on new constructions.31

By 1907, the tenement market was over-saturated and demand was falling. The construction of new tenements had dropped by 70% compared to 1906 – the speculative property boom of previous years had finally flattened. The mortgage market no longer favored borrowers, the interest rates were high and lenders also demanded higher levels of security. Tenement builders in Manhattan and the Bronx were further pressured by the improved transit services to other areas of the city.32

In mid-October 1907, just weeks after the Co-op had reorganized its portfolio, a financial crisis hit the US with the NY stock exchange dropping 50% from its peak in the previous year. In Harlem, bank runs forced two state banks to close and savings banks enforced laws requiring depositors to give notice on withdrawals. Although the banks were solvent, a general panic had spread.33

The crisis caused thousands of immigrant banks to fail across the US and depositors lost their savings. The resulting high unemployment and increased emigration rates among the working class further lowered the demand for new tenements. Life insurance companies and savings banks almost entirely withdrew from the lending market for several months leading to higher interest rates on loans that were already hard to obtain.34

It’s unlikely that the Co-op was financially robust enough to navigate a flattening property market during an economic downturn.

The Secret Service received tip-offs that held a more cynical viewpoint. They claimed Giuseppe Morello had purposefully caused the Co-op to fail and destroyed all the accounting records. They also accused Morello of causing the “Societa Bentivegna” to fail. The accusations were repeated in the writings of William Flynn, head of the New York Secret Service.35

According to the Co-op’s directors, the troubles were linked to its Bronx construction project.

Antonio Milone explained that every person involved, with the exception of Lupo and Morello, lost their money after investing in the E 138th Street property. Although co-operatives were meant to be democratically controlled, Milone stated that Morello never took him into his confidence and that Morello’s word was taken as law when running the business.36

Di Miceli, the financial secretary, testified that shareholders injected as much capital as they could afford with Morello making up the shortfall. They agreed to sell the property to Lupo as the highest bidder. Di Miceli then left the company after receiving no wage. He was succeeded as secretary by someone named Fatta, likely the same Fatta that managed Lupo’s grocery store accounts. (Lupo’s daughter, Onofria, later married a Gaetano Fatta in 1934).37

In January 1908, the flagging Co-op was still working to complete the apartments on E 137th Street. By March it was struggling to repay the $50,000 borrowed from associates, so it diverted the rents it received to the lenders to help cover the loan. However, four months later, Carmelo Naso filed a foreclosure on the mortgage he had granted the Co-op.38

In May, the Bentivegna Company had mortgages on four of its E 126th Street tenements foreclosed by same lender that funded the Florio Co-op. The Bentivegna Company was dissolved the following year.39

On October 30th, Pietro Inzerillo was served with foreclosure notices on both of his E 138th Street tenements.40

According to statements from people close to Giuseppe Morello, it was around mid-to-late 1908 when he hatched a plan to reimburse his investors with counterfeit money. Co-op director Antonio Milone, who was an experienced photo engraver, etched the counterfeit printing plates for Morello.41

“It was Morello who conceived the idea of counterfeiting the notes on a large scale. Sometime after the Co-operative Association failed, some of the members who had lost their money began to crowd Morello and threatened to kill him. Morello’s idea was to reimburse these men with counterfeit money.”

In November, Lupo leased both his E 138th Street tenements to Antonio Rizzo. (Most likely the same Rizzo who, in 1903, had purchased the Prince Street saloon from counterfeiter Andrea Romano and was also questioned in court regarding the ‘Barrel Murder’.42) Lupo then took a $13,000 mortgage on his properties from Joseph Di Giorgio a wealthy fruit importer. At that point, Lupo’s buildings were mortgaged for a total sum of $71,000.43

In an apparent scheme to leverage his failing properties before they were repossessed, Lupo used the buildings to secure large amounts credit for his Manhattan grocery business. He fled New York in late November leaving behind debts of approximately $100,000 as part of an organized conspiracy.44

The police say [Lupo] furnished the security upon which the groceries were stocked. The scheme was started by securing a house valued at more than $75,000 on which Lupo paid $3,000 and gave a mortgage. By referring this house as security, the backers of the grocery chain got credit in lots of $2,000 until they had $100,000 worth.45

In early 1909, Lupo was judged to be bankrupt. Joseph Di Giorgio and other lenders filed foreclosure suits on his mortgages.46 Giuseppe Morello, who had been living at #630 E 138th Street, vacated the property in early February 1909.47

Legal procedures against the E 137th Street properties began in April. By June, the New York State Supreme Court summoned Lupo, Morello and others to appear in regard to the E 138th Street tenements, at least one of which was put up for public auction. The Co-op’s other properties on E 140th Street were sold at auction with over $42,000 debt still owing.48

Giuseppe Morello was arrested for counterfeiting in late 1909. He was sentenced to twenty-five years at Atlanta Penitentiary. Lupo, who was arrested in the same case, received thirty years. At the time of his arrest, Lupo was with Carmelo Naso and Salvatore Saracino, the Directors of “The Co-Operative Society of Sicily”. Saracino was also jailed for counterfeiting.49

Shortly after Morello’s arrest, the Secret Service searched the home of Giovanni Di Miceli at 241 E 108th Street. They had been tipped-off that some of the Morello gang’s counterfeit notes were hidden in a grain store at the address.50

Co-op director, Antonio Milone, was arrested in late 1911 under the suspicion that he had etched the counterfeit printing plates used by the gang.51

The Co-op continued to face legal battles with various money lenders in the following years. In 1912, the E 137th Street tenement’s new owners found themselves in court after the Central Union Gas Company claimed that the cooking ranges they had installed had never been fully paid for.52

When Morello was questioned in prison regarding the The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative, he said it no longer existed and he could not recall any details.53

The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative

Author: Jon Black

Published: December 2023

- “The Real Estate Market in 1907″ / “Mortgage Money in New York” / “The Construction of New Buildings in 1907″/ “Tenement Construction in 1907”. (1908) Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. Vol.81 [↩]

- The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi. Certificate of incorporation. (1902) [↩]

- Justin Cascio. In Our Blood: The Mafia Families of Corleone (2023) p157[↩]

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter referred to as NARA), RG 87, Daily Reports of Agents, (hereafter referred to as DRA). New York Vol. 33. p.517,555-557, 589, and other pages – see volume index for Milone.[↩]

- Marriage certificate #8008. Manhattan, NYC .

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Badolato-27 (Accessed Dec 2023)

Polk’s New York City Directory (1915) p.1167 & (1916) p.211[↩] - Warner, Santino, Van`t Riet. “Early New York Mafia An Alternative Theory” The Informer. May 2014. Thomas Hunt. p.45

New York City Directory. Vol.114 (1900) p.327[↩] - Paolo Orlando is not the Brooklyn Mafia leader of the same name.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.73 Jan-Jun (1904) p.401

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.79 Jan-Jul (1907) p.888

New York Times. Sep 30, 1906.

Directory of Directors in the city of New York. 1907/08. p.14, 114, 225, 481

New York Herald. Mar 30, 1907. p.5

NARA. DRA. Richard H. Taylor. Vol. 4. p.430[↩] - Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891 – 1931. New York: Routledge. p.46

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Macaluso-119 (Accessed Dec 2023)

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Parisi-100 (Accessed Dec 2023) [↩] - The Trow (formerly Wilson’s) copartnership and corporation directory of New York City (1906) p.248

The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi. Certificate of Incorporation. (1902)

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Di_Miceli-169 (Accessed Dec 2023)

Marriage certificate #27903. Manhattan NYC.[↩] - U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Guiseppe Calicchio et al, Transcript of Record. Giovanni/Morris DeMiceli testimonies.

Marriage certificate #27903. Manhattan NYC.[↩] - New York Times. October 4, 1905. p11

The Trow (formerly Wilson’s) copartnership and corporation directory of New York City (1908) p.78[↩] - Societa Co-operativa Corleonese Francesco Bentivegna. Certificate of Incorporation. Filed 28 April 1891.

Polk’s (Trow’s) New York copartnership and corporation directory, boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx (1895) p.306[↩] - NARA. DRA. William Flynn. Vol.9. p.204 -207

Day, Jared. (1999) Urban Castles. Columbia University Press.

Ramsey W. K. Immigrant Banks. (1910) United States. Immigration Commission (1907-1910) [↩] - Day, Jared. (2002) Credit, capital and community: informal banking in immigrant communities in the United States, 1880–1924

Day, Jared. (1999) Urban Castles. Columbia University Press.[↩] - Ramsey W. K. Immigrant Banks. (1910) United States. Immigration Commission (1907-1910) p.109[↩]

- NARA. DRA. William Flynn. Vol.9. p.204 -207

NARA, RG 129.6 Records of the U.S. Penitentiary, Atlanta, Inmate Case Files, 1902–1922. Giuseppe Morello

Flynn, William J. (1919) The Barrel Mystery. James A. McCann Company. p.184[↩] - The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi. Certificate of Incorporation. (1902)

This figure is at odds with the original incorporation which showed 50 shares. There may have been prior shareholder adjustments.[↩] - Day, Jared. (1999) Urban Castles. Columbia University Press.[↩]

- Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.74 Jul-Dec (1904) p369, p453, p449

Not to be confused with the Mafioso Stefano La Sala of the same name. See: The other Stefano la Sala by Justin Cacio – https://mafiagenealogy.com/2017/03/20/the-other-stefano-la-sala [↩] - New York Herald. March 23, 1904. p2[↩]

- Manhattan NB Database 1900-1986, NB 271-1905 (Accessed Dec 23)

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.77 (1906) p.253

Year: 1910; Census Place: Manhattan Ward 12, New York, New York; Roll: T624_1015; Page: 25A; Enumeration District: 0337; FHL microfilm: 1375028

Gallucci’s previous home was 339 E 109th where he ran a cigar store and factory.

New York Times. January 11, 1906. p.14[↩] - Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Jun (1906) p.1088

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Nov (1906) p.898

Manhattan New Building application # NB 642 – 1906[↩] - Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Dec (1905) p.1067

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Oct (1905) p.604[↩] - New York Times. June 30, 1905. p.13.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.76 Jul-Dec (1905) p.1001

New York (N.Y.). Commissioners of Accounts. (1908). A report on a special examination of the accounts and methods of the office of the President of the Bronx (1908) New York: Martin B. Brown Press. p.17-18[↩] - Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.79 Jan-Jul (1907) p.720[↩]

- Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.80 Jul-Dec (1907) p.499[↩]

- Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.80 Jul-Dec (1907) p.505, 644

Black, Jon. The Grocery Conspiracy. 2013. https://www.gangrule.com/events/the-grocery-conspiracy. (Accessed Dec 2023) [↩] - Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.80 Jul-Dec (1907) p. 497, 505[↩]

- Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.82 Jul-Dec (1908) p.216

The New York Herald. 25 July, 1908. p.2

The Trow (formerly Wilson’s) copartnership and corporation directory of New York City (1908) p.182

Certificate of Incorporation. #792/1906C[↩] - Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.80 Jul-Dec (1907) p.644, 732[↩]

- “The Real Estate Market in 1907″ / “Mortgage Money in New York” / “The Construction of New Buildings in 1907″/ “Tenement Construction in 1907”. (1908) Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. Vol.81 [↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panic_of_1907

The Event Post. New York. Oct 24, 1907. Front Page[↩] - Day, Jared. (2002) Credit, capital and community: informal banking in immigrant communities in the United States, 1880–1924

“The Real Estate Market in 1907″ / “Mortgage Money in New York” / “The Construction of New Buildings in 1907″/ “Tenement Construction in 1907”. (1908) Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. Vol.81 [↩] - NARA. DRA. William J Flynn. Vol.28 p.282, 283 / Vol.29 p.264

Flynn, William J. (1919) The Barrel Mystery. James A. McCann Company.[↩] - NARA. DRA. New York Vol. 33. Various pages – see volume index for Milone.[↩]

- U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, The United States of America vs. Guiseppe Calicchio et al, Transcript of Record. Giovanni DeMiceli testimony.

Marriage certificate #13954 & #9280. Brooklyn NYC.[↩] - Central Union Gas Co. v. Browning, 146 A.D. 783 (N.Y. App. Div. 1911)

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.81 Jan-Jul (1908) p.583

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.82 Jul-Dec (1908) p.216

The New York Herald. 25 July, 1908. p.2[↩] - Lender: John A. Philbrick & Bro’s.

The Sun. New York. 10 May, 1908. p.14

New York Tribune. 13 May, 1908. p.8

The Trow (formerly Wilson’s) copartnership and corporation directory of New York City (1909) p.73[↩] - Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.82 Jul-Dec (1908) p.864[↩]

- NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn (Feb 10, 1913) Statement of Salvatore Cina

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn Vol. 28. p.906. Comito the counterfeit printer claimed he was first approached by the group in late October 1908.

NARA. DRA. New York Vol. 33. p.517, 518[↩] - Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.82 Jul-Dec (1908) p.1097

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.69 Jan-Jul (1902) p.934

The World. New York. May 7, 1903. p.5[↩] - Records of the Office of the Pardon Attorney. NARA Record Group 204. 230/40/1/3 Box 956. Ignazio Lupo (NYPD news clipping file) [↩]

- Black, Jon. The Grocery Conspiracy (2013) https://www.gangrule.com/events/the-grocery-conspiracy. (Accessed Dec 2023) [↩]

- The Evening Telegram. New York. January 11, 1910[↩]

- New York Times. Jan 22, 1909. ‘Business Troubles’

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.82 Jul-Dec (1908) p.1289

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.83 Jan-Jul (1909) p.227, 525.[↩] - NARA, DRA. William J Flynn. Vol. 28. p.1115[↩]

- Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.83 Jan-Jul (1909) p.824

New York Tribune. July 6, 1909. p.11

New York Times. Oct 4, 1909. p.15

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide. Vol.83 Jan-Jul (1909) p.1267[↩] - Certificate of Incorporation. #792/1906C

NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn Vol. 28. p.987. Joe Palermo was the pseudonym of Salvatore Saracino.[↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn Vol. 28. p.217, 240, 381

Address: United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925. (M1490) Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925. 511 [↩] - NARA, RG 87, DRA. William J. Flynn Vol. 33[↩]

- Central Union Gas Co. v. Browning, 146 A.D. 783 (N.Y. App. Div. 1911) [↩]

- NARA, RG 129.6 Records of the U.S. Penitentiary, Atlanta, Inmate Case Files, 1902–1922. Giuseppe Morello[↩]