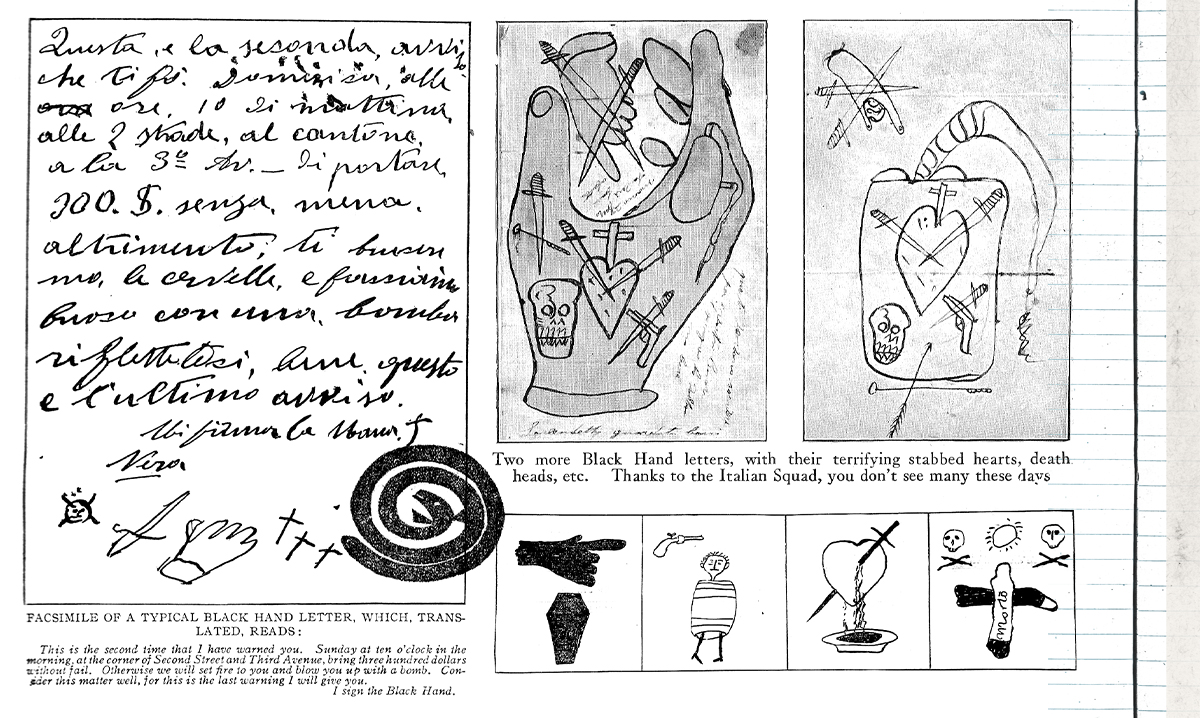

“A letter shoved through the crack under a door or dropped in a tenement letter-box, bearing the dread symbol of the Black Hand and the signature La Mano Nera, and containing a demand for money under threat of death or disaster. A few weeks later, if the demand in the letter is ignored, a knife-thrust in the dark, or, the explosion of a crude bomb. That is the Black Hand.” – Everybody’s Magazine (1908)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

During the last decade of the nineteenth century more than 650,000 Italians migrated to America, with a further two million following over the next ten years. The majority came from Italy’s impoverished southern regions, where half the adult population labored in unrewarding agricultural jobs. They were drawn by America’s enormous demand for unskilled labor and its reputation as a land of wealth and opportunity.1

Many Italians found passage to America through the exploitative padrone (boss) contract labor system. Immigrants were promised assistance with travel and employment but were often held under conditions of servitude once they arrived. The padrones who acted as middlemen between the workers and employers would secure their labor at a low wage before renting them out to other contractors. Padrones found as many ways as they could to control the workers’ money, over-charging them for accommodation, provisions and banking. The practice was slowly outlawed in the last half of the nineteenth century, and padrones began to disguise themselves as bankers or employment agents. Immigrants were given instructions as to what they should say to pass immigration control and were warned to distrust every American they met.2

Life in the new world was tough. Many immigrants found it necessary to travel from city to city to find work. Housing conditions were often cramped and unsanitary. Rents in New York could cost as much as 50 percent of an unskilled worker’s wage.3

One of New York’s worst slum areas was Mulberry Bend.

“In the scores of back alleys, of stable lanes and hidden byways, of which the rent collector alone can keep track, they share such shelter as the ramshackle structures afford with every kind of abomination rifled from the dumps and ash-barrels of the city …Something like forty families are packed into five old two-story and attic houses that were built to hold five, and out in the yards additional crowds are, or were until very recently, accommodated in sheds built of all sorts of old boards.” 4

Some immigrant communities showed little division of class or status, with laborers, the unemployed, skilled and professional workers inhabiting the same space. In 1881, journalist Charlotte Adams wandered the streets of New York’s Little Italy and remarked on the contrast she had seen5,

“Some of their homes were low, dark rooms, neglected and squalid; others were clean and picturesque … from the neat and graceful poverty adorned with bright colors, to the dens of one room, in which three or four families live. They told me that the building contained a thousand souls.”

On August 3, 1903, wealthy Brooklyn contractor Nicola Cappiello received a letter demanding $1,000 or “your house will be dynamited and your family killed” signed Mano Nera (Black Hand). The letter resulted in the first Black Hand case to make the headlines and marked the beginning of a new term applied to extortion and violent crimes in Italian neighborhoods over the next decade.6

Why Cappiello’s extortionists chose Black Hand as their brand is not known, but the name had undoubtedly been popular among global criminal groups in the previous decade.

Some suspected it was taken from a Spanish society active in 1874, while others claimed it came from the Camorra in 18257. Other groups included a Belgian gang of murderers known as The Black Hand that was broken up after a sensational trial in 18948; A “notorious Black Hand society of Anarchists and firebugs” operated in New York around 18949; The fictitious tale of a Black Hand killer stalking the streets of Guadalajara in 1897 was magnified until it “equalled Jack the Ripper in London.”10; In 1898, a Puerto Rican secret society of thieves and murderers used a Black Hand symbol to mark their victims doors.11

In 1902, prior to Cappiello’s case, a play titled The Black Hand toured American theaters. The production was based on the real-life murder by a secret society that left a Black Hand symbol pinned to the body. A stenographer fled the play’s production office after cards had been jokingly mailed to staff bearing the message “Beware the Black Hand!”12

Extortion by anonymous letter with the threat of dynamite and threats targeting wealthy Italians were both crimes that had been seen in the US before. However, used together under the name Black Hand, these became a potent new menace.13

Reports of Black Hand cases spread rapidly, with newspapers giving conflicting explanations of the outbreak. Some reporters believed it was a “secret organization more dreaded than the Mafia” or that it was an offshoot of the Sicilian Mafia spreading through American cities. Others disputed the existence of any society at all, claiming Italians had been fleeced by swindlers who simply found the US a safer place to commit their crimes.14

Although Italians in New York City and Chicago had the highest percentage of personal violence, blackmail and extortion offenses when compared to other groups, the sensational nature of them was often “expanded in print under headlines that catch the eye.”15 Giovanni Schiavo stated that, in Chicago, “the so-called Black Hand only exists in the imagination of reporters in search of sensationalism and of police officials incapable or unwilling to solve a crime.”16 This view was supported by the Italian consulate, which conducted its own investigation into Black Hand allegations. The consulate found that twenty-nine out of thirty cases had logical explanations unrelated to a Black Hand conspiracy theory.17

In 1908, the annual number of Black Hand cases reported in New York reached 424 with forty-four bomb explosions. In 1913, the number of explosions across the five boroughs approached 100 within just the first seven months. The struggling NYPD had only forty Italian speaking officers, four of which could communicate in the Sicilian dialect but “are of only limited usefulness because they so quickly become known to the criminal Italians.”18

Due to a similarity in extortion methods and the reluctance of victims to give evidence, the police believed that Black Handers were closely aligned with the Mafia and quickly started to refer to them as a “Society.”19 Over time, the terms Black Hand and Mafia became almost interchangeable to the press and government agencies.

No large centralized Black Hand Society was ever discovered, and only a small number of organized groups were exposed. An article in 1909 explained,20

“While there is little organization among the Italian desperadoes in the United States, the title of Black Hand, conferred upon them by the newspapers, gives them an advantage never before possessed by scattered lawbreakers … the individual adventurer need only announce himself as an agent of the Black Hand to obtain the prestige of an organization whose membership is supposed to be in the tens of thousands.”

Some Mafiosi did gravitate toward wealthier Italians in their communities, exploiting widespread fear of the Black Hand. “Boss of bosses” Giuseppe Morello repeatedly offered his services as a mediator between the Black Handers and their victims and was said to have “made much money settling the frightened of letters.”21 He acquired the gratis services of a family doctor after acting as his negotiator and was suspected of secretly extorting his own attorney, thinking his arbitration could lead to lower legal fees.22 Brooklyn boss Sebastiano Di Gaetano was described by detectives as a “go-between” for a ruthless Black Hand kidnapping gang and it’s victims.23

William Flynn of the Secret Service described the way in which the Mafia leader used the letters, adding a slight twist to the more simplistic methods of lesser criminals:24

“A threatening letter is sent to a proposed victim. Immediately after the letter is delivered by the postman Morello just ‘happens’ to be in the vicinity of the victim to be, and ‘accidentally’ meets the receiver of the letter. The receiver knows of Morello’s close connections with Italian malefactors, and, the thing being fresh in mind, calls Morello’s attention to the letter. Morello takes the letter and reads it. He informs the receiver that victims are not killed off without ceremony and just for the sake of murder. The ‘Black-Hand’ chief himself declares he will locate the man who sent the letter, if such a thing is possible, the victim never suspecting that the letter is Morello’s own. Of course, the letter is never returned to the proposed victim. By this cunning procedure no evidence remains in the hand of the receiver of the letter should he wish to seek aid from the police.“

Contents of some of the Black Hand letters found in Giuseppe Morello’s home:25

“MR. BATAGLIA: Do not think that we are dead. Look out for your face; a veil won’t help you. Now is the occasion to give me five hundred dollars on account of that which you others don’t know respect that from then to now you should have kissed my forehead I have been in your store, friend Donate how you respect him he is an ignorant boob, that I bring you others I hope that all will end that when we are alone they give me no peace as I deserve time lost that brings you will know us neither some other of the Mafia in the future will write in the bank where you must send the money without so many stories otherwise you will pay for it.“

“DEAR FRIEND : Beware we are sick and tired of writing to you to the appointment you have not come with people of honor. If this time you don’t do what we say it will be your ruination. Send us three hundred dollars with people of honor at eleven o’clock Thursday night. There will be a friend at the corner of 15th Street and Hamilton Ave. He will ask you for the signal. Give me the word and you will give him the money. Beware that if you don’t come to this order we will ruin all your merchandise and attempt your life. Beware of what you do. M. N.“

“FRIEND: The need obliges us to come to you in order to do us a favor. We request, Sunday night, 7th day, at 12 o’clock you must bring the sum of $1000. Under penalty of death for you and your dears you must come under the new bridge near the Grand Street ferry where you will find the person that wants to know the time. At this word you will give him the money. Beware of what you do and keep your mouth shut…“

Several instances were recorded of individuals practicing Black Hand crimes who would later join the Mafia. These included Jack Dragna, future boss of the Los Angeles Crime Family, and Bonaventura “Joe” Pinzolo, who went on to lead a Bronx-based clan that became the Lucchese Crime Family.26

In 1907, a society called the “White Hand” was formed in Chicago. Backed by the Unione Siciliana, the Italian Chamber of Commerce and the Italian consul, it was the first systematized effort by Italians to defeat the Black Hand threats. However, the society eventually faded away after its leadership faced extortion and death threats.27

A similar effort was started two months later in New York. Under the guard of police detectives, 500 Italians held a meeting at the office of Italian newspaper Bollettino della Sera. They agreed to create an organization called the Italian Vigilance Protective Association, made up of thousands of trusted Italian volunteers with subcommittees throughout New York. It was intended to aid the police with localized intelligence from the community.28 The same evening, NY Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham announced his plan for a secret detective squad to battle the Black Hand. Funding for his squad was refused by the city’s aldermen, and the idea was criticized by politician “Big Tim” Sullivan. Bingham was forced to seek private donations.29

Lt. Joseph Petrosino, who was to head the squad, gave his views on the Black Hand criminals:30

“There is only one thing that can bring about the end of the Black Hand and that is enlightenment. The Italians who keep Little Italy in fear and trembling are generally from Sicily and Southern Italy. They are transplanted rustic-brigands. Their work is surprisingly crude. No New York highwayman would think of holding up a man in the streets of New York and cutting his face with a pencil sharpener to frighten him into turning over his money. Nor would a New York crook dare to threaten to dynamite the place of business of a man if he did not appear at a certain time with a certain amount of money. The crimes committed here among the Itallans are the same that are committed by country brigands in Italy and Sicily, and the victims are the ignorant people. It is a rustic brigandage existing in the streets of one of the greatest and most civilised cities of the world.“

Bingham’s plan was halted in 1909 after Petrosino was assassinated while in Sicily gathering intelligence on Italian criminals. The NYPD Italian Squad, formed under Petrosino’s leadership, was later reduced to just four men.31 Extortion and kidnapping crimes began another dramatic rise in New York, with 151 recorded arrests for bomb-throwing in 1913. Two years later, however, offenses had dropped by 70 percent. The application of updated policing methods by the new NY Police Commissioner Arthur Woods, stricter extortion laws and a drop in European immigration during the Great War all contributed to the slow decline of the Black Hand phenomenon that had raged for the past twelve years.32

- Varese, Federico. (2011) Mafias on the Move. How Organized Crime Conquers New Territories. Princeton University Press. 104

Grossman, Ronald. (1975) The Italians in America. Lerner Publications. 13-15Sassone, Tommaso. (1922) Italy’s Criminals in the United States. Current History 15. New York Times Co.

Foerster, Robert F. (1919) The Italian Emigration of Our Times. Cambridge: Harvard university press. 49-50

Willcox, Walter F. (1931) International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations. Italian Migration Movements, 1876 to 1926. NBER. 456 [↩] - Hall, Prescott Farnsworth (1906) Immigration and its Effects Upon the United States. New York: H. Holt. 131-133

Letter from the Secretary of the Treasury, in response to the Senate resolution of June 12, 1894, calling for facts in regard to the padrone system. Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office. [↩] - Bulletin of the Department of Labor (Mar 1897) No.9. The Padrone System and Padrone BanksHall. Immigration and its effects upon the United States. 131-132

De Forest, Robert W. (1903) The Tenement House Problem. Vol.2 New York: The Macmillan company. Appendix IX. Tenement House Rentals [↩] - Riis, Jacob August (1890) How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York. New York: C. Scribner’s sons. 55, 65 [↩]

- Gabaccia, Donna (1992) Little Italy’s Decline: Immigrant Renters and Investors in a Changing City. In, Landscape of Modernity: Essays on New York City, 1900-1940. Russell Sage Foundation. 240-242

Adams, Charlotte (1881) Italian Life in New York. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Vol.62 (No.371) New York: Harper & Bros. 680-682 [↩] - Pitkin, Thomas M. & Cordasco, Francesco. (1977). The Black Hand: a chapter in ethnic crime. Totowa, N.J: Littlefield, Adams. 15–16

New York City press (Sep–Dec 1903) [↩] - New York Times. Sep 27, 1903. p32 / The Topeka Daily Capital. Sept 22, 1903. p4[↩]

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Aug 5, 1894. p1[↩]

- New York Tribune. Oct 21, 1894. p1[↩]

- The Buffalo Commercial. Mar 22, 1897. p7[↩]

- Buffalo Evening News. Dec 7, 1898 [↩]

- New York Times (Aug 18, 1902)

Courier Post (Sep 9, 1902)

Detroit Free Press (Jul 23, 1902)

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Dec 1, 1901) 21 [↩] - The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Dec 1, 1901) 21

Richmond Dispatch (Sep 28, 1902) 1 [↩] - The Cincinnati Enquirer (Dec 3, 1903) 1

The San Francisco Examiner (Dec 6, 1903) 1

Brooklyn Times Union (Sep 19, 1903) 2 [↩] - United States. Immigration Commission. (1911) Immigration and Crime. 61st Congress. Document 750. 17-22

Lord, E., Barrows, S. J., Trenor, J. J. D. (1905) The Italian In America. New York: B.F. Buck & Company. 216 [↩] - Schiavo, G. Ermenegildo. (1928). The Italians in Chicago: a study in Americanization. Chicago, Ill.: Italian American publishing co. 130 [↩]

- Abbott, Grace (1917) The Immigrant and the Community. New York: The Century Company. 119 [↩]

- New York (N.Y.) Police Department. (1908). Annual Report of the Police Department of the City of New York. New York: New York Printing Company.

White, Frank Marshall (1913) The Black Hand in Control in Italian New York. The Outlook. V104 New York: Outlook Co. 864[↩] - St Joseph News Press Gazette (Dec 9, 1903)

Brooklyn Times Union (Nov 30, 1903) 4 [↩] - Critchley, David (2009) The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. New York: Routledge. 23

White, Frank Marshall. (1909) How the United States Fosters the Black Hand. The Outlook. V93 New York: Outlook Co. 497[↩] - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter referred to as NARA), RG 87, Daily Reports of Agents, (hereafter referred to as DRA) William Flynn. Vol. 29 (Feb 27, 1910) [↩]

- Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 31-32

NARA. RG 87. DRA. William Flynn. Vol. 28 (Dec 13, 1909) [↩] - The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Dec 9, 1910) 2 [↩]

- Flynn, W. J. (1919). The barrel mystery. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.[↩]

- Flynn, W. J. (1919). The barrel mystery. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.[↩]

- Critchley. The Origin of Organized Crime in America. 26-31 [↩]

- The Missoulian (Nov 19, 1907)

Des Moines Tribune (Nov 19, 1907)

Chicago Tribune (Aug 18, 1908. Jan 28, Apr 3, 1911) [↩] - Burlington Daily News (Jul 27, 1908) 6

Chicago Tribune (Feb 7, 1908) 4

Harrisburg Telegraph (Mar 12, 1908)

New York Daily Tribune (Feb 7, 1908) [↩] - The Brooklyn Citizen (Apr 22, 1908)

Norwich Bulletin (Feb 20, 1909) 1 [↩] - NYT. Dec 30, 1906[↩]

- The Brooklyn Citizen (Jun 22, 1911)

Brooklyn Times Union (Jun 30, 1911) [↩] - New York Tribune (Jun 23, 1911) 7

Harrisburg Daily Independent (May 20, 1913) 3

The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer (Jun 22, 1916) 3

Pittsburgh Daily Post (Feb 12, May 21, 1913) [↩]